Rob and Josef talk podcasts, and comes clean about his awkward intro to Nick Moran.

Nick talks about his path to becoming a General Partner of New Stack Ventures and the host of The Full Ratchet podcast. We talk decision-making as investors, and advice for founders, including the most common mistake: building a product then trying to find a market for it. Then dive in to address the problem of matching opportunities to investors, whether it’s founders pitching VCs, or VCs pitching institutional investors.

Rob and Nick connect as founders-turned investors, while Josef jokes about the Insane Clown Posse in a truly additive and valuable fashion.

Not really.

Who does Nick see executing? He calls out two companies that have pushed through the pandemic, Flamingo and Tripscout.

Full Transcript Below:

00:00

Welcome to execution is king, the Great North ventures podcast. Today we’re joined by general partner of new stack ventures, Nick Moran. He’s also the host of the full ratchet podcast. With me today also his general partner of Great North ventures Rob Weber. Thanks for having me, guys. This is such a pleasure to be here, Rob. Always good to see ya. Thanks

00:21

for joining us, Nick. First starters, talk a little bit about how you became a venture capitalist. And also tell us about a little bit about your work with the full ratchet.

00:31

Yeah, you got it. I mean, we’ve talked in the past, it was a bit accidental. This is my second career. So I started out in corporate America, doing m&a, you know, scouting out early stage tech companies to buy through a roundabout series of events, I ended up being an entrepreneur within this organization taking a product to market over three years, working with a large r&d team of 30. And we had sort of extraordinary success with that product. I was a beneficiary of that success and was able to sort of leave corporate america and, and figure out my next path in life as a young man when I was about 32. So I moved back to Chicago with my wife, I started angel investing and, you know, fell down this rabbit hole of venture and startups and, you know, how do you build the next transformational multibillion dollar tech company? And yeah, through that series of events launched the full ratchet, I think it was, maybe at best a clever hack to network with some folks on the coast. At worst, you know, it was just kind of a fun program for me to learn. And it really worked out. I mean, I think I was early to the podcast thing and got lucky. The audience sort of exploded, you know, before there were 1000s and 1000s of podcasts. And that resulted in a lot more deal flow than I knew what to do with and sort of snowballed into this investing for newstagged. ventures.

02:06

And you’re up to almost, is it almost 300 podcast episodes so far? Is that right?

02:11

Yeah, I think so. It’s probably more than that between we do these special segments in between episodes. So I can’t imagine how many we have total. But I would bet how it gets it’s more than 500 at this stage.

02:22

Yeah, it’s really impressive. I was just talking with Nick before the show about these great episodes he does with investor stories, that are just great little bites. So if you have a minute, check out the podcast, that episode I’m talking about the last one is about 11 minutes long. And it sees for investors giving post mortems on these companies that failed. And it’s just as super interesting, especially like the example around the one that failed due to COVID. Because it just this excessive headwinds and stuff. But there’s some great points from Great Investors on that podcast, urge you guys to check it out.

03:00

Yeah, I think part of the context that makes your experience, Nick, as he talked about it, you know, so interesting is having been on both sides of the table, you know, building a product, and then spending all this time interviewing all these investors, and then, you know, actually running a fund. But you know, especially as we think about, like, the product side, that’s kind of the background that my brother and I had before we started getting more adventures, you know, after, you know, spending so much time in this space. What are some of the takeaways you have, you know, for new founders, you know, in terms of product development? What are some of the common mistakes that you see, or what advice would you have, and I know, your fund is kind of in the pre seed seed stage was very early, in fact, earlier than probably a lot of other venture funds. What would be some of the advice that you would give to, you know, a first time founder who’s building their first product?

03:52

It’s a good question, I think, sort of classic mistake that still the majority of entrepreneurs make, even though we’ve we’ve said this advice over and over again, Rob, you and I have talked about it is, you know, they build a product and then look for a market later. Actually, just last week, we were talking about this episode I did with Dharmesh stacker from battery, right. And he was saying one of the weaknesses with doing investments in serial entrepreneurs. So folks that started and had success with a tech company from a previous generation is often those types of founders from you know, that learned in an old generation of tech, they often want to build super powerful tech, and then go out and you know, find a market for it. try and convince customers that this is the solution to all their problems. And in the modern world, in the modern tech world. That’s just not how things work. You need to prove value up front. You need to deliver ROI and value super fast. I think Dharmesh, his rule is in 90 seconds or less, you know, the end user needs to understand why this is transformational for them and makes their life better. And so we’ve seen this big shift to a focus on customers focus on needs, you know, what are the key problems that you’re facing in your work life or in your consumer life? And then how do we reverse engineer a solution that really delivers on on that problem? So if I were to give advice to the early stage founders, it would be you know, become obsessed with your customer, find your ICP, your ideal customer persona, spend time in a market, discover the key insights, you know, what are the key challenges facing that market, and then figure out how to build a solution that meets the need, you know, don’t just just because you’re a developer, and you’re a talented builder, that doesn’t mean you should go out and build some super powered tech, and then just assume that the market is going to love it.

06:02

Do you think that’s a consequence of tech really exploding out of, you know, the confines of being its own sector, and just kind of taking over every sector? that that that shift away from just being able to build something great, and then figure out a way to sell it, versus having to build to actually fulfill these needs?

06:22

Is that Yes, I think so. Joseph, I think it also goes a little deeper. I think it’s a mindset issue. And I think it’s, it’s the victim of arrogance, right. So we all have a bit of confidence, and maybe maybe a shred of arrogance, some more than others. But when you are arrogance, you believe the world operates like yourself, you believe that the mindset of the consumer base is much like yourself. And so you think that if you can build something, that’s your ideal product, right? That’s your ideal technology that ever the market will come? Right? If you build it, they will come? The reality is that, you know, if you’ve met one consumer, you’ve met one consumer, right? There’s a lot of shapes and sizes, there is no one size fits all anymore. That just doesn’t work. And so you need to figure out, you know, what are the segments within the market? What are the consumer groups, or the buyer groups within b2b that have a similar philosophy or ideology or buying behavior or need set, and you need to you build products that really serve a problem and serve a need. So I think it’s a problem of mindset. And it’s folks thinking that the rest of the world operates like themselves. And that’s just not the case.

07:42

It’s interesting, I do think there’s a sort of fine line between self confidence and being open to feedback, right. And I think in entrepreneurship, like you kind of have to have a balance, I think the best entrepreneurs app have developed that strong customer empathy. So they can kind of wreck, you know, they can take the feedback loops, and kind of, you know, bake that into their product development. It does take a degree of self confidence, though, because you can’t have every, every single feedback session or artifact, you know, can completely push you off your strategy. So it’s kind of a fine line of being a good listener, but also having, you know, some confidence in finding the right path forward. Right. And when you are building out your products in the past, like how much do you stock? Do you put in just like the systems for startups? Like, are your real vocal proponent of kind of lean startups and all the, you know, systems behind that? Or are you kind of take a more like open approach to, you know, in terms of the systems that these entrepreneurs are utilizing to kind of bake their strategy or their product development?

08:50

Yeah, that’s a tough one, I would say, Yes, I am a proponent of the lean startup, but more at the theoretical and philosophical level, I think some entrepreneurs can get maybe too caught up in the tactics, and you know, the details with that and chase their tails a bit. I mean, to your point before, you can’t be so wishy washy, that all feedback from customers finds its way into the product. Right? We like to say that when we’re selecting founders, or we’re investing in founders, we like to find people that are incredibly stubborn about their vision, but incredibly flexible about the path to get there. Right. So you need to have a really strong vision, here’s where we’re going. But you need to be incredibly receptive to the market in the customers and how the product actually manifest in the path. To tie this back to my experience with the product. I’ll give you a simple example. Right? I was building a handheld device, right? It was a handheld device for measuring compounds in drinking water. So things like monochloramine or chlorine or nitrate or iron, right. And a huge number of the customers That I did testing with said, I would like this to be touchscreen. Right? We launched this product in 2013 ish timeframe. And there was a big proponent of customers that said, I really need this to be touchscreen, right in the markets that we’re testing. Well guess what the reality is, there’s a lot of cold weather climates, where people are doing this testing on the back of a pickup truck in sub zero degree temperatures in places like Minneapolis, or Chicago. And they’re doing it with huge gloves, and big parkas and a hat and goggles. And you can’t have a touchscreen device in that environment. So this is just one simple example of the overwhelming feedback was we want touchscreen. But when you look at the markets we’re going to sell this product into it was not a viable decision for the product, right. And so that’s just one small thing. Like you need to collect all the different information from the customers, but it’s the job of the product manager to decide on the solution. Right? It’s the customers that surface the problems, the product manager needs to find a solution that most appropriately services the market.

11:13

That’s really interesting. Well, yeah, bringing up, you know, kind of the Midwest in Chicago. I know, that’s where you’re based. Can you describe a little bit about your experience, since you moved back to Chicago? What is the startup ecosystem like there? For those who are unfamiliar?

11:29

It’s exploding. I mean, I’m not on the ground in Minneapolis, I’m sure you’ve seen things really develop and evolve in your ecosystem. But in Chicago, I got back in 2012 2013, in 1871, had just opened, which is sort of the incubator startup Mecca. Within Chicago, we were really just finding our footing on becoming, you know, a real sort of call it a second tier tech ecosystem, not not on the level of San Francisco, New York, but a major player, right, we had had some big exits, we had some big successes, and that had spurned some talent in the ecosystem that went and started more companies. So now, you know, during the past almost 10 years, geez, it’s developed quite a bit, you know, there’s more venture capital firms than ever before. There’s more startups being funded than ever before. we’ve really seen the ecosystem progress for the better, and sort of hit its stride. So I think Chicago is only going to go from here. But you know, if you go back to the time I started investing, there was very few pools of capital. And we kind of, we had our choice of the startups we wanted to invest in now. It’s, it’s, it’s more competitive, which is better for everyone involved.

12:55

I was really impressed. When I went back to Northwestern in February, pre COVID. For venture capital events. I had gone to school at macdill. So I haven’t spent a lot of time at Kellogg, but when I went there, they have this fabulous new building, which they were just building when I was at Northwestern. And it was just a beautiful setting right there on the lake, the field. And it was full of all kinds of people. Betsy Ziegler was there from you mentioned 1871, some other people, all kinds of great funds represented there, mingling with just these top level up and coming VCs, out of Kellogg, and just being in that spot. And that’s not even that’s up in Evanston. That’s not in the heart of anything, which, from my experience is more towards 1871 would be kind of the heart of a lot of this action, while at least downtown in general will be more towards the heart of it. But it was super impressive. It really gave me some hope for what what we can aim for here. You know, like getting that vision, getting that idea, that vision for Minneapolis and what the ecosystem can aspire to be.

14:04

Yeah, it’s really great. I mean, you’ve cited the university’s Stanford and MIT their efforts are well documented and the stratix accelerator at Stanford, you know, one of the most prominent in the country. But look, look at Northwestern, you mentioned them, they’ve got the Wildcat challenge and look at Chicago Booth. They’ve got the NVC the new venture challenge, which I believe kicks off tomorrow on the third of June. This has become the Chicago Booth one has become one of the preeminent accelerators in the country. That ranks right up there with the YCS and Angel pads, right? The successes from that program, you know, the winners of Chicago, Booth NVC, our grub hub, Braintree tovala, I mean, you know, hundreds of millions, if not billion dollar companies that have been enormously successful. So it’s it’s really nice to see that the academic academic institutions have structured themselves in a way to really promote true Entrepreneurship, that is the challenge when you get into academia, you know, is this going to be more of a research or learning exercise, there’s this really, you know, a capitalist endeavor. And I think what we found is the Chicago based institutions have figured it out, and, you know, created some really transformational, you know, large scale tech companies. So we’re looking forward to meet and some more tomorrow at the competition, and at a future Northwestern event as well.

15:29

I think it’s really interesting, Nick, I’ve been building software companies, either as an was started off as an entrepreneur, and then an investor, the last, you know, I don’t know, 15 years, but 25 years as entrepreneur, all in Minnesota, and really, you know, from when I got started, there was very little support, there weren’t organized, you know, communities for startup competitions, accelerators, you know, maybe there was one or two venture funds, you know, now there’s, you know, just in the Twin Cities market, there’s well over a dozen early stage funds. And then we have, you know, it’s a little different in Minnesota, the University of Minnesota, I think it’s a little over 10 years old, we have a Minnesota cup, which is actually kind of built for all startups in Minnesota, it sort of lives, you know, on the campus of the University of Minnesota, but it’s not just for the U of M students. So it’s kind of interesting, I think it’s, it’s evolved a bit differently. But in many respects, I think the last decade is really brought just incredible wealth of support for entrepreneurs starting to build things. Of course, I think one of the main areas that entrepreneurs that are looking to get discovered are looking for support is on fundraising. And you know, despite the emergence of what 1500 plus venture funds around the country, you know, getting that first round of capital for many is still really challenging. And I know you’re, you’re one of the few funds that you know, invests in kind of pre seed, and then also what I’ve called, like, really early seed stage companies in the Midwest, I know you invest all around the country, what are some of the signals you look for? Or what are some of the things that you would in terms of advice would pass along to founders, you know, in terms of raising that first round of venture capital?

17:08

Well, first of all, you need to know where to aim. Right? Like before you launch a process, and before you start pitching. And before, you know you do your dog and pony show with a bunch of investors, you have to understand your ICP. Just like if you’re launching a product into a market, right, who’s your ideal customer persona. And for a fundraise is the same Rob, you just mentioned, like in the Midwest, there are seed stage investors series A investors pre seed, some will do pre traction, some won’t. Some will invest in hardware, others won’t write some, like consumer, some have a preference for b2b. We’ve got a whole crop of Life Sciences folks, right? There’s a lot of shapes and sizes to these investors. And if you just roll out of bed with a really cool product, and you know, a little bit of sales, and do your rounds in sort of Minnesota ecosystem with whoever you can get an intro to, you’re probably going to find some mismatches, right? It’s like the dating app. And you know, you’re you’re dating somebody from a different culture that doesn’t speak your language. And it’s like, where do we even begin here? So you kind of have to know where to aim. Figure out what type of startup you’re building, right? What are the sectors you appeal to? What are the technologies that you’re building around, you know, Ai, blockchain, etc? Who are the markets that you’re serving? Right? Are you serving certain demographics with your startup, let’s say, the boomers or Gen Z, for instance, or you know, maybe your startup is focused on women. And then the stage, of course, the stage is important, the geo is important. So there’s all these filters and structures that investors use to kind of think about your startup. Here. Again, it’s like sector, market technology, geo stage. And if you are honest with yourself about which boxes you check, you can find the ideal set of investors that is just well designed for your startup. Right. There are generalists that just invest in Minneapolis startups, there are specialists that just invest in AI powered startups, right, you need to know who those investors are first. Rob, you and I have discussed this tool that we built VC dash rank.com. It’s a simple questionnaire that startup founders can fill out in five minutes or less about their startup. And they generate a customized list of all the ideal early stage investors for their startup. I think we have somewhere from 15 to 30. Startups filling that out every day. So it ends up being you know, you add those up over time, there’s a lot of startups out there looking for investors, but if you’re aimed in the wrong direction, you know, you’re gonna waste a lot of your own time. In founders time is the most important thing when you’re building an early stage startup.

19:57

I think that that’s a lot a source of a lot. VC hate that you see, I mean, there is plenty of legitimate criticism about VCs, there’s there’s bad behaving VCs, don’t get me wrong. But I think that that point you just made, that it just being a mismatch, that people going into every what should be a speed date with the intention that they want to get married, without actually realizing that they need to make sure that that’s going to be a good match. I think that that manifests itself and justly so in people getting incredibly, you know, frustrated by that process, and then taking it out against just the industry in general. It kind of obfuscates a lot of the legitimate criticism of the industry, though, and and makes people you know, it makes it harder to uncover. Because when the problem is that source, what’s the real problem? It’s hard to uncover when it’s just simply a mismatch from the beginning.

20:54

100% Joseph, and I’m getting a taste of my own medicine, right, because as we embark on on raising our next fund, we’re not raising currently, but as we do that, we need to meet with the right investors for us, right. In our industry, we call them LPs limited partners. But I need to know who are the institutions that like to invest in emerging funds, right? Who are the institutions that like funds in the $50 million size range? Who are the institutions that have an interest in the middle of the country investing versus coastal, right or international, right, if I don’t do my homework, on my own ICP, then I end up spinning my own wheels with a bunch of folks that you know, want to cut billion dollar checks in the multi billion dollar funds that are focused only on San Francisco, and I’ve just wasted their time in my own. So, you know, this, this has got many different levels of extra abstraction, whether you’re a startup selling a product, you know, founder trying to, you know, sell your business, sell equity in your business, or a venture capitalist that’s, you know, trying to raise a fund.

21:55

And just some advice to anybody out there who’s going to turn around and Google ICP to figure out how to proceed, ignore the first results, or any results with pictures of crazy clown makeup. That’s the wrong result for you. Wow, flashback there. Now we’re showing our age.

22:12

It’s really interesting, Nick, when I was a sort of founder turned investor, you know, I was like you as an angel investor for a while, while while I was sort of founder, took the success as an angel investor became a VC. And the number one request we have, from founders we back is, can you help me complete my round? Or can you help me connect other capital sources, and to me is like a founder turned investor, it’s like, the least interesting thing I could help a founder with, is just finding more capital, I’d rather go deep on like product goes to market, you know, human resource and operations, like how do you scale the growth of the company? Not so much like, Hey, can I i’ve this spreadsheet, I started with 200. Plus, it’s just people in the last four years that I’ve talked to you that are involved in the VC game, and I did use the VC dash rink comm tool that you built for internal startup we had been incubating called next jam, it’s really, really useful to kind of filter down across these different dimensions, who are the funds that we should be talking to? And I think a lot of founders, it’s not even so much as like getting an intro to the funds, like, I know that a lot of the funds that we should be talking to, but they weren’t necessarily the ones top of mind for me. So just having a filter to say yes, these are the ones that based on, you know, some kind of database are probably the ones that are right for you and make some ton of sense to me. So I think it’s super valuable. I’d love to see more startups using this. And it wouldn’t solve this, like signal and noise issue when what you really want is like relevant deal flow that can make right you know, the speed for fundraising faster, right. 100%.

23:46

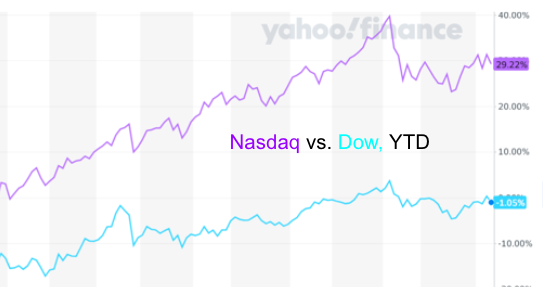

I mean, it’s, it’s amazing to your point, how network driven and opaque the whole fundraising landscape still is, it’s always based on referrals. And you have to have the right networking etiquette. I mean, if you go back to the origins of VC, it was a little cottage industry, you know, country clovers, and people that were insiders, Sharon deals. And that’s kind of where this industry began. But, you know, as we move forward in time, it’s institutionalized. I mean, tech is no longer, you know, a footnote in the asset class universe tech is sort of leading and driving the returns, both in privates and publics. And so I think we’re gonna see our industry, our asset class, really professionalize and become more tech fold. Right? It shouldn’t be this old insider game of who you know, and who can I get an intro to and, like, you know, can I can I get the royal treatment from the investors at benchmark I mean, amazing, firm, right benchmark, but they they don’t have a website, right? You have to know somebody to kind of get in there. And honestly, I think that’s the model of the past. I think it’s gonna die. The future is about you. Technology Solutions media, you know, having a systematic process, it’s it’s not about who you know, it’s about what you can build.

25:08

And increasingly, it’s not about where you’re located either. I mean, that’s starting to not matter at all, which used to be hugely important for VC. And even when you look at VCs who do business all over the world or across the country, you know, that geography that they do more deals, where they’re located, then states further away, like if you’re based in DC, or even if you’re based in Chicago, you know, there might be a way more deals in Silicon Valley, but you’re going to be doing more deals in Chicago, just because that’s who you run into. But increasingly, that’s becoming less and less important.

25:44

Well, I think, you know, one of the effects of COVID is no longer do I have discussions with investors that say, oh, middle of the country, investing the Tam’s too small, like the outcomes aren’t going to be big everyone? Well, not everyone, but the vast majority of folks out there realize, wow, there’s talent everywhere, you know, whether it’s talent that left the coast that moved other locations, or just the reality that great, huge, multi billion dollar tech companies are being built everywhere. We’re seeing that more and more every day, which is, it’s nice not to have to face that objection anymore. Oh, Minneapolis. Oh, yeah. No good tech companies are gonna come out of there. Chicago. Yeah. You know, you guys have your strengths, but it’s not technology. Yeah. Okay. Let’s look at you know, the cameos of the world and, and you know, these other huge successes. So it’s no longer an objection, we really have to face which is nice.

26:39

So Nick, I know, you take a very systematic approach to venture capital, kind of pioneering how to use tools and technology to make the process more efficient. I saw this survey a few months back that ranked from founders seeking capital, the number one criteria or attribute that they cared about the most was speed. Yeah, and I know you’ve interviewed a lot of funds, are there, you know, from a systematic standpoint, are there certain things you found to really speed up the investing process? Or is there any any other venture funds that, you know, obviously speeding, making a quality decision that times are enemies of each other? Right? Like, you know, how do you have you? Have you found ways to move faster in decision making, or across the VCs that you’ve interviewed? Any that really stand out to you on this dimension of speed?

27:27

Wow, that’s a tough question. Yes, we have implemented a lot of systems and processes, I can talk about that when to your ladder question on any VCs in particular, I would say that the VCs that stand out, as being great at making decisions quickly, are solo capitalists, largely, you know, when an individual is doing the meetings with the founders and can decide at first meeting or second meeting. Look, this person has the right ingredients, you know, like you’re taking all these data points, they’re mixing up in your head, we talked about this abstract concept, pattern recognition. But honestly, a lot of at bats in this industry over time, you start to figure out here are the things that I like, and you process all these data points, and you make decisions. So it’s the solo capitalists that can move quickest, because, you know, there’s no infrastructure, there’s not multiple people, there’s not, you know, a whole series of diligence. When it comes to our firm. We are not that, right. So we have a number of people at our firm that can do deals. It’s not just Nick Moran, right. And I’ve been very clear with my folks here in New sec from the beginning, this will not be the Nick Moran show. This is newstagged ventures, we are building a scalable venture capital firm. And so what we’ve had to do is get very, very clear about what we’re looking for. We kind of divided up into three segments. So when we’re looking at a deal, we look at the who, the what, and the how. So the who is the foundation, that’s the people behind it, the talent, their raw capabilities, their you know, their raw mindset. The what is kind of the business is the business, the industry, the sector, the product, is it, you know, scalable? Is it venture scale is an interesting does it have tailwinds and then the How is sort of the framework that the founders are using to access that market, build the right product. Think about you know, how we wedge into the market? How are we focused on customer needs? To that point, we did you know at the top of the interview or are we tech first. So the How is like the process that the founders are going about to access the opportunity. And then you know, at New stack we think very specifically about what are our must haves. What are important to have and what are nice to haves and across each of those three, the who, what and the how we’ve been very specific about what those three are. So we have must haves on every deal. If a must have Isn’t there we pass, we have our important hands on every deal, if a certain percentage of important to haves aren’t there, we pass. And then we have our nice to haves as well. And so that’s our attempt at taking all these patterns and all these factors that we’re vetting for, and actually codify them into a process that can be taught to young folks, you know, as we have this fellowship program of 20 young folks across the country, undergraduates, and it’s too hard to spend the next you know, five years with all of them and try and teach them all these abstract patterns, we have to codify them, we have to get very specific about here are the factors to be looking for, so that their learning curve, you know, moves quicker. And the end effect of that, Rob, is that we should be able to make a decision on a founder, and investing in that founder in less than two weeks, hopefully, less than one week. But if we know what we’re looking for, and who we are as a firm, and you know, what types of founders are positioned to succeed in a partnership with the SEC, then we can move more quickly.

31:04

I just said one more kind of a more narrow question around this process and system you have I know, one of the things they talk about in venture capitalists kind of decision making is this notion. It’s like a psychology notion of, they call it confirmation bias. And I know I’ve experienced I’ve had to sort of fight myself against is that time where I see it, even in our partnership, like the more time you spend on a deal, there’s a tendency to look for evidence to support, you know, your initial interest in that deal. And so you have this self fulfilling kind of confirmation bias to do a deal as you dig in more and more and more. Have you had any, you know, with this sort of more in this sort of system that you have? Do you have any sort of guardrails against like confirmation bias? Or have you ever felt like you’ve experienced that? And, you know, or how do you avoid confirmation bias?

31:53

It’s a good question. I don’t know, if we have an answer to that, if I’m being honest, I do know that we’ve gotten incredibly late stage in diligence on deals. I mean, I even flew with, with my deal lead to Colombia, the country to do diligence on a deal and spent two entire days, you know, in the field, like meeting with customers and whatnot, we ended up passing because something came up late stage and diligence that violated my staff. And we had to have a real honest conversation about that. And, you know, as I think about scaling this firm, I think about, you know, we need to use these moments as teaching moments of how we got to make decisions. And even if it’s even if it’s so much easier to proceed with the investment at that point, because the sunk cost is there. And the confirmation bias, is there. the right decision, if we really want to build a best in class firm, that’s going to produce great returns, and teach folks how to say no, even when you’re over committed, is you got to say no, when, when it’s right to say no. And I learned that the hard way working for dinner for years in m&a, a very aggressive acquire My god, I would do diligence on 1000s of companies, I would spend, in some cases multiple years, getting to know founders of different companies and visiting them in Spain and Italy and all around the states. And then those deals would fall apart. And so yeah, that was a painful reality in our business. I mean, we’re meeting with founders, you know, for weeks or months. And so to pull the plug on those for me is like, you know, that’s nothing. It might be harder for the younger people. But for me, it’s nothing compared to multi year. relationships.

33:39

Yeah, totally. You bet that your prior experiences is super helpful in that regard. So I think Joseph, you had a kind of a final question, right? Oh, yeah.

33:49

Yeah. So our last question here, like to ask all of our guests who come on the show, can you tell us about someone or a startup that you’ve observed executing at a really exceptional level, maybe someone in your portfolio or someone outside of your portfolio, but someone you’ve seen maybe who isn’t getting recognition for that, but who’s really killing it? There’s too many to choose from.

34:15

Maybe I’ll pick a couple that were slammed hard by the pandemic. I mean, terrible categories for the bat pandemic. One is Jude chewy, he runs a company called Flamingo. Flamingo serves the multifamily property industry. And it’s a it’s an events focused platform. And that thing, I mean, the events out of the business went to zero effectively last, I think, April or May. This guy is just a rock star. He built a SaaS business alongside his events business during the pandemic, grew it to the size of the events business. I mean, remarkable MRR and now the events have come back and so now he’s got I mean, it’s kind of amazing but he’s got a you know, two sided, you know, dangerous multifamily software business that does both events and, and software as a service, which are super complimentary for what he’s working on. And it’s just been amazing to see the resiliency. I mean, it would have been very easy for him to shut it down. And many of my LPs reached out and said, Is God gonna survive? And I said, if you ask him, there is no quit here. There is no, you know, pulling this business up and just super proud of him. Another one is Conrad Wallace Xu scheme in MDX at at a business called trip scout. This is a travel business that serves consumers and just got crushed, absolutely crushed by the pandemic. Many travel companies went out of business, many large travel public businesses just are on the ropes like the TripAdvisor is of the world. And these guys have just made magic of, of the situation. It’s, it’s unbelievable, how they doubled down created more content and special guests. You know, created a almost like an Anthony Bourdain, like series on travel during the pandemic, travel from home, you know, everyone’s stuck inside. How do you get the experience of being on a trip when you’re at home? And coming out of the pandemic? they close? I think they recently closed 4 million bucks from accomplice, I mean, tier one VC there. I mean, they are on this upward trajectory, like I haven’t seen. And it’s it’s kind of amazing. You know, there was never quit, there was never hesitation. There was optimism, despite a really tough situation. So those are two I would, I would just, you know, tip my cap to them. I’m glad and proud to be an investor in people like that more so than than anything. Trip scout and Flamingo. We’ll have to check those out. All right. Well, thanks

36:53

a lot for joining us today, Nick. It’s been a pleasure and best of luck as you continue to grow, you know, new stack and thanks for you know, launching VC dash rank.com. And the other work you do to support entrepreneurs and founders and of course, the podcast, which is one of my faves. So thanks for joining us today.

37:12

Yeah, thanks, Nick. Make sure you check out the full ratchet, visit the new stack website. They’ve got some great tools for founders on there.

37:20

Such a pleasure to be here guys. Thanks for having me and love the pod Keep it up. Can’t wait to see who the next guest is.

Ryan and Josef talk about the importance of startup communities and the importance of innovation in rural communities, including St. Cloud, MN.

Molly shares her experience working with incubators, builders, and startups with Singularity University and how that led to her position as the Entrepreneur Ecosystem Development Lead at CORI, where she works with communities to build the infrastructure necessary to help entrepreneurs succeed. Molly paints a picture of a rural America in decline, and explains the transformative value generated by tech startups and productive tech startup ecosystems.

She explains that the key to any ecosystem is putting the entrepreneur at the center, and calls out Red Wing as a startup community that is really executing- as well as every rural community they work with. “That’s the stories that need to be told. Those are the underdogs that we need to be uplifting. Those are the people flying under the radar that I could talk about all day.” “We have so much more to go as a country in terms of entrepreneurship, in terms of innovation than just what we see in these five major metro areas.”

Full Transcript Below:

00:00

Welcome to the execution is king podcast. Today I’m talking with Ryan Weber, managing partner of Great North ventures. And joining us as a guest is Molly Pyle, the entrepreneurial ecosystem development lead at the center on rural innovation. I’m Molly, how you doing today? Hey, doing well, how are you? Good, good.

00:22

Hey everyone, Ryan Weber here in greater St. Cloud, Minnesota for my home. It’s late June 2021. And we’re starting to see things open up quickly as our vaccination rate Minnesota exceeds 50%. I moved to the St. Cloud from the Twin Cities in 1998 to attend college. The population here is around 189,000. While in college, my partner at Great North ventures Rob and I bootstrapped a company and online PC software publishing and later, ad tech focused on smartphone app marketing to 170 employees and eventual and exit. You know, at Great North ventures, we think execution is key to success. And this podcast will hope to help founders and investors learn best practices from others building the next great global startups from wherever they may be. And I’m really excited today through the work at Great North ventures I’ve had the great fortune of interacting with Corey and some of the work they’ve been doing with ecosystems in the region. So Molly, could you start off by telling us a little bit more about your background and what Korea is?

01:28

Yeah, definitely. So I got started working in entrepreneurship, working with startups, running incubators and accelerator programs at a company called Singularity University based in Silicon Valley. And I had this amazing privilege to get to work with global entrepreneurs see incredible ideas and innovators from truly everywhere, every corner of the earth, you can imagine folks would come and participate in this program that helped them, leverage these exponential technologies and build them into scalable tech startups. So that made me really fall in love with the opportunity that entrepreneurship provides for people. No matter where you come from, if you have a good idea, you can turn it into something real and impact billions of people potentially. So with that sort of becoming my professional focus, I learned about the center on real innovation, which is just a really compelling organization for me specifically, as I wanted to see entrepreneurship as an opportunity become more accessible to more people. So the center on real innovation is an organization that’s really dedicated to closing the rural opportunity gap that emerged out of the Great Recession. I joined the organization in August, like Joseph mentioned as the entrepreneur ecosystem development lead. And that’s really just a long way of saying I help rural community leaders build startup communities and entrepreneur ecosystems. And what that means is building that infrastructure that’s necessary to help entrepreneurs thrive to help aspiring entrepreneurs who have an idea, but maybe don’t know that they can take it forward and execute it. Figure out who are the people who are the programs? Where are the partnerships, what can I access that can help me actually create this tech startup, even if I am in Red Wing, Minnesota, or Cape Girardeau, Missouri, for example. So these uncommon places that you don’t often hear about, as you know, innovation and tech hubs, but center on real innovation really believes that they can become these kinds of tech hubs. And part of that why is why are we focused on rural America specifically, it’s because to be frank, it never recovered from the 2008 recession. So the urban and suburban communities really bounced back rural places failed to replace the jobs lost in that recession, let alone grow their economies. And then we all know the effects of COVID. Nationally, globally, no matter where you are, who you are, we all felt the impacts, but in rural, specifically, only 5% of tech jobs even before COVID were in rural areas, despite the same regions representing 15% of our national workforce. So all of this very unequal recovery stems from what we’re seeing the automation of jobs, so many of which were originally in rural like agriculture, manufacturing, globalization, so outsourcing some jobs that could ultimately be done by Americans if they were skilled up to be able to meet the needs that those jobs require in terms of skills and talent, and this 30 year decline that we’ve been seeing in entrepreneurship. So that’s why we’re really committed to creating sort of inclusive ownership of production in the age of automation.

04:35

That’s great just for framing today’s conversation a little bit Can you talk about for corys focus? Can you define what you mean by entrepreneur and what you mean by rural?

04:46

Yeah, totally. So rural, we talk about like a community in the population size of 5000 to 50,000, which may seem even bigger than you might think but something that we think is important is trying to Create, whether it’s through regional partnerships or through technology as well, the density that rural communities in rural areas lack, that you just naturally have population density in an urban area. So we think about rural in this way, we try to encourage the communities that we work with to take more of a regional approach and think about how they can leverage technology to build more of an ecosystem and inclusive culture. And entrepreneurs, you know, anyone with an idea who is actively working on turning that idea into a startup, and we specifically focus on folks interested in building scalable tech startups. And we do that because there are lots of organizations incredible organizations like score and co starters and the SBDC and local communities that will help folks with a main street or small business or sometimes called a mom and pop kind of business idea. And we acknowledge that that kind of entrepreneurship is critical and is a backbone to really the American economy. But what we want to see is scalable technology startups being created in rural communities, because we’ve seen the returns that those kinds of companies can have in terms of jobs, in terms of wealth being created for that community. So seeing those kinds of impacts, helping people create tech startups, also the rise of distributed work and remote teams being something that you can do, you know, build and scale a startup in rural Maine. And you could have some team members in other hubs where there’s more tech talent, perhaps, but doing that, helping bring the jobs helping bring the wealth and create that in a rural community. That’s our goal. That’s what we’re really focused on.

06:36

Right? Can you share a little bit more about what community needs to be successful? Is there a checklist of must haves that you have put together?

06:46

Yeah, so I mean, the first kind of obvious thing, which I am proud of and want to share about the center on real innovation is one of the things we do as well is help communities to apply for federal funding. So the basic funding that you need to stand up and build an incubator, for example, or get the funding to run an accelerator program or a hackathon, all of that has to start somewhere. And we support real communities and applying to this federal funding. And I’m very proud to say since 2019, only, we’ve helped communities raise more than 13 million in federal funding and match dollars. So the first kind of thing I would say is, while there’s no checklist, it’s it’s pretty obvious that you need, you need capital, you need an infusion of capital, you need folks willing to invest in the community to build the basic infrastructure for an entrepreneur ecosystem. And you know, there is no replicable formula that you can take and drag and drop. We’ve seen some things work in some communities and not working others, but ultimately to one of the most basic things in addition to just having some infusion of capital, whether it’s federal funding, or investors or a mix of that public private partnerships, is also just access to connectivity to high speed internet. So just to illustrate, and part of what Cori does, as well, another bridge organization is support communities and accessing broadband and getting broadband set up. So for example, a recent Deloitte analysis of the digital divides economic impact showed that a 10% increase in broadband access in 2014 would have produced nearly 900,000 more us jobs, and 168 billion more in economic output in 2019. So that’s, that’s kind of, I think, a really powerful statistic to show how important broadband is to economic development and particularly, to building entrepreneurship ecosystems in tech startups. If you’re again, trying to hire remote, you know, DevOps team, and you’re in whatever rural community you may be in, that’s where you love. That’s where you want to be rooted and build your business. If you’re having trouble connecting to the internet and chatting with your team on zoom, which, as we’ve seen, is such a lifeline to doing work in the 21st century, you know, the chances of your success are really limited. So starting with broadband at the most basic level, starting with capital to help you actually build out some of the physical and, you know, otherwise infrastructure that you need for programming. That’s super, super important. And then I also think it’s really, really vital for tech entrepreneurs, especially in rural areas to see visible success stories of people who look like them, who come from their community, who have made it who have been there done that, even if they failed once or twice, I would say that’s even better. Because there is this mindset of, you know, this can’t happen here. There’s this fear of well, if I try and I fail, then everybody knows me, I’ll I’ll have to run into people at the grocery store and kind of hide my head and shame. And I think that we need to really blow up that idea and celebrate the failures, which is something I think I jokingly say Silicon Valley maybe has over indexed in doing but in rural communities, we can kind of bring it back down to It’s okay. You have the courage to actually go out there and try something. And we should be celebrating you and highlighting your efforts to try to build something amazing in this community and for us and for us to be proud of. So get back out there, try again, amplify the voices of people doing this, put them on platforms, do speaker events, do tech talks, do things that the community can come in open to the public and engage because these types of things, I think, plant that seed, and shift the narrative that oh, this can’t happen here. So that’s really important. And also that leads to more that leads to you know, I go to a tech talk, I hear from an entrepreneur, who has actually made it in my rural community. And that suddenly inspires me, I can do this. Now, what do I do? What’s the next step? So having a sort of clear pathway of you go to a tech talk, you hear someone who’s made it who’s from your neighborhood? And then you think maybe this is for me? Well, where do I get started? Who can help me? Are there programs are there incubators are their mentors are their angel investors. So building all of those basic next steps for an entrepreneur to have a sort of cohesive journey, I find that that’s really, really critical. And that’s something I work a lot with our rural community leaders on developing that journey for their entrepreneurs.

11:11

So where do you see communities like starting out? Do you have like leaders come to you who are working on building that infrastructure? Or do you see it beginning with entrepreneurs trying to do a tech startup and then reaching out when they when they have, you know, things that they need that they’re not able to come up with?

11:31

Yeah, our model is working with the community leaders. So the people at that ecosystem building layer, maybe their managers or directors of incubators, co working spaces, accelerators, or general, you know, entrepreneur innovation hubs, maybe attached to a university, we work with that layer of folks to ultimately build their capacity and their ability to serve their local entrepreneurs. So trying to keep things really deeply rooted in the community because someone who has been managing the CO working space in you know, platteville, Wisconsin for five years knows much more than I do about who you should talk to and where the mentors are, or what investment may have happened two years ago with this other successful startup. So we try to help those community leaders actually be the most effective that they can for the entrepreneurs. However, I will say I, I’m a big fan, probably no surprise to anybody in the startup world and Brad Feld and Ian Hathaway in the book, startup communities, I’ve been reading that and doing a book club, actually, with the real community leaders on it. And there’s a piece in that which I love. And I always try to drive back home, which is this philosophy of keeping entrepreneurs at the center, everything in the startup community in the ecosystem should revolve around entrepreneurs at the center, what do they need? What are they looking for? How can we best be of service to them? So trying to apply that lens to the work we do with the community leaders is really front and center of ultimately, everything I’m doing is saying, Are you talking to entrepreneurs just like how we tell entrepreneurs? Are you talking to customers? Are you getting out there in the field? Are you asking questions? Are you iterating, based on what they’re telling you, the ecosystem builders and the people serving entrepreneurs need to also have an entrepreneurial mindset. They need to be flexible and adaptable, they need to respond to the changes of what the entrepreneurs are saying they’re needing or what’s working or what’s not working for them. So trying to really help them adopt that mindset and be the best possible, you know, supporters and fans and amplifiers of their local tech entrepreneurs. That’s really, again, what I think we are all about, ultimately, are the work that I do.

13:43

I got a shout out our advisor Scott Resnick, at this point. He’s he wrote a portion of a chapter or maybe it was a whole chapter I forget in the startup community, his book. He’s EIR at starting block in Madison, Wisconsin doing all kinds of good ecosystem work in Madison.

14:03

That’s really interesting, Molly, you know, I was thinking back to when we were starting there. You know, it’s obviously a larger market, but we had entrepreneur success stories. And that was a major inspiration. And I think more recently, I’ve heard about tech successes and other smaller markets, like Ben from Douala into Moines. He’s got very become very active in the ecosystem in Iowa. And Zach, founder a jam that went public in Eau Claire has done so much to help, you know, you know, ignite, you know, a spark there in Eau Claire. And, and I think that’s something people don’t realize is that there are six very successful tech startups that are being formed, you know, all around the country in the world right now. But these markets are a little bit bigger than the markets you’re targeting. I’m really curious to hear are there any markets or startups kind of entrepreneurial success stories that you could share from these smaller rural markets that you’ve engaged in started working with?

14:54

Yeah, so I, I mentioned this community earlier, and I love talking about that. Because they are a, you know, real underdog that’s come up and hence a massive success, and that is Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and this is a community 40,000 in population 25%, poverty rate 25%, lower median income household in the population. So it’s a region and an area that had been in decline in all the ways you can think of and university attendance in their some of their main industries being manufacturing. So the two entrepreneurs locally, who decided to do something about this, James and Chris, they opened, codify, which is a co working space, an innovation hub and tech incubator in Cape Girardeau, which is in Southeast Missouri. And they started this competition called the first 50k, which is ultimately aimed at attracting tech startups to the area and ultimately giving them $50,000. If they agreed to stay in that area for two years and build their company there. And they provide lots of value mentorship, they actually have a in house project shop, and an adult coding boot camp where they’re building the tech talent pipeline as well. And that’s another big thing in terms of what do entrepreneurs particularly in rural need is access to tech talent, right? So beyond hiring remotely, if you can find local tech talent within your community, that’s fantastic. And so keep Gerardo the codify folks were really trying to solve for that building out the tech talent building out the program to bring entrepreneurs, and they had some really interesting learnings in that program, and found that there were some folks who, you know, came participated, got the $50,000 for two years and then left. And that’s obviously not what they want, they want to find people who are going to stay and become rooted in the community and really, you know, give back and stay there for as long as their startup is scaling and growing and in business. And what they found is that that was actually a real goal of one of their entrepreneurs show rust of a company called show.ai, which is a sort of AI and digital marketing firm, which is just rapidly now scaling, super successful. And part of it is because show, he was doing the startup thing in LA, he was, you know, scaling and getting a lot of traction and saw the first 50k competition as an invitation to return home. He had had family he had had, you know, community and connections in Cape Girardeau, and thought that that was always maybe a place that he would like to return to and be closer to his community. But he didn’t think that there was anything there in terms of, you know, startup activity, mentors, investors, people who could support him. So he was living in LA trying to build that out. However, he saw this first 50k competition, he realized, while people or people in my hometown are trying to make it happen, actually, there’s there’s activity, there’s vision. So he applied, he won, and he has been there ever since. And he’s actually a company that our firm, the Corey Innovation Fund, actually a branch of our organization has invested in so we have a fund that invested in qualified opportunity zone startups startups based in those opportunity zones, which Cape Girardeau is. So show being back in that opportunity zone, being back in his hometown with his family, building his tech startup that was you know, doing great in Los Angeles, but now continues to thrive in Cape Girardeau. I just love that story. And I think it’s a great example of finding, finding that personal connections, people who are gonna return to a place or move to a place or stay in a place because there’s something you know, that really roots them there. I think that is really special and really notable. And I just have to add that part of the first 50k program, why I love it, and think it’s impactful is if you can find those people who are going to stay, of course, beyond the two years, that’s the goal, who have this reason or vision for saying in the community. What that has happened is seeing the awardees, seeing those startups generate over 6 million in revenue, create 40 plus local jobs, and generally, again, prove to the community be visible that this is possible that this can happen here. So ultimately, I think that that is one success story. But the program itself is so much more impactful. I think when you look at that big zoomed out view of how many jobs and how much impact and how much of a mindset shift it’s creating for folks in Cape Girardeau.

19:25

Yeah, that’s really interesting. You know, I, I hadn’t heard details of that story, but I can only imagine how transformative that is to a community like that. And, you know, there’s, you know, you know, a couple of people I wanted to get kind of shout out and in our region, you know, in Sioux Falls Matt Polson, of marketbeat, a founder has really taken a leadership role along with local other entrepreneurs and consulting groups to really shape Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and it’s really a it’s become a statewide initiative. It’s really connecting communities around the state to supercharge startup entrepreneurship and In North Dakota, you know Greg Tevin and advisor in our fund, with emerging prairie in the grand farms initiative, they’ve got a plug and play now in partnership with Microsoft building the future farm itself, you know, these are larger markets, but you would, it would just blow your mind how connected these communities are and how these entrepreneur and ecosystem leaders together can really make a difference quickly and in and that’s what, you know, in your story. It resonates that speed at which, you know, a small group of people in a smaller market, when aligned can really, really change the trajectory of a community quickly. And that’s one of the real, you know, positives, there’s obviously no, there’s some of the challenges that we discussed earlier. You know, speaking of challenges, what are some of the lessons learned, you know, what are unrealistic expectations? What are some of the past failures that we might learn from, from some of the work you’ve seen?

20:52

It’s really important, like, I like I had mentioned that tenant of keeping startups and keeping entrepreneurs at the center of everything. So anytime that there is a story of a pitfall or a failure, I tried to think about, well, what were the symptoms or the factors that caused this and almost every time, I would say, if not every single time, it’s when governments or other actors, stakeholders, people kind of outside of the direct sort of center of entrepreneurship are trying to exert control, trying to impose their views from the top down, rather than letting the entrepreneurship ecosystem be really bottom up, be led by entrepreneurs. So architecting out, entrepreneurs from leadership is the most, I would say accelerated way you can lead an ecosystem to fail, if the entrepreneurs are not the people at the center, making decisions, having their voices heard, having their needs being met. I think that that is something that, you know, will be a fast track to pitfalls. And, and I think that all too often, too, there is this expectation of these kind of actors or investors at the maybe government or other level who believe that there is such a thing is an overnight success story. And while there are there are definitely people who can move fast and break things, as they say, all over this country, and particularly in rural areas as well, because I really believe that innovation and being resourceful is kind of at the heart of a lot of people in rurals mindsets and attitudes, you had to be innovative and resourceful to survive in rural America really, for so long. And so I think that when you can see, you know, folks not understanding that this is also a long term commitment. This is a long game, like, you know, Brad Feld says think of it in 20 year segments. So when folks are expecting overnight success and have a misalignment of expectations of Oh, we want to see your first accelerator ever that you’ve done in, you know, rural Vermont produce the next Google, that’s obviously not realistic. However, it doesn’t mean that there can’t be fantastic startups coming out of these areas. And these programs, it just means that we need to in tech startups, for that matter, it’s it’s definitely our focus, like I mentioned, but it’s something that I think we need to get on the same page about early on is that this is going to take, if you’re starting from scratch, especially a longer time, you’re going to need to really stick with it to be okay, like I mentioned with the failures that you might see at first, and to understand that this is something that will happen over the course of like Cape Girardeau, that kind of massive impact and all of the, you know, millions that they’ve generated, and the hundreds of jobs that have been created beyond that first 50k program, they also have, you know, tech startups being built just within their space, all of that happened over the span of now seven, seven years or so. So it’s it’s not something that can happen within six weeks. But it’s also you know, something that I think we can stay optimistic about because it can happen, it just may look a little different than you might imagine it would in Silicon Valley. And that’s okay. I don’t think we need to recreate the next Silicon Valley, I think rural communities can create their own thriving startup ecosystems that fit with the culture in the context. So ultimately, I think it’s about keeping that in mind.

24:18

That’s really interesting. You mentioned a few of the success metrics, like job creation, and you talked about, you know, upskilling, you know, the labor, you know, workforce, but also, you know, attracting, you know, you know, skilled talent back to a region. You know, are there any other metrics that are qualitative or quantitative things that you use as measures of success? Because, you know, this is a can be a grind, and you have to, it may take a long term, but what are some of the things that you would any other anything else you might suggest focusing on, you know, for measuring the progress that’s being made?

24:50

Yeah, I mean, we definitely do look at access to capital as a indicator like like every startup ecosystem, but particularly how die The situation is in rural, that we’ve found and research shows that less than 1% of all VC money goes to rural areas 80% of all investments are made in just five major Metro cities. So tracking and looking at and supporting, how are how the companies in these rural communities are raising capital, whether it’s through traditional investment, capital micro financing grants, we’re trying to support them in all the different ways in blends that they can access capitals. So helping them do that. And tracking that is a huge metric. It’s also you know, the the, the equity investments that they can get from that wanting to see that it’s the exits we’ve had and seen a few exits a few IPOs, a few acquisitions. So trying to track all of that, but also, you know, just the the general startups if you’re starting really small, that are participating in your incubator. are you growing that number over time? Did you start off with five companies in your incubator or accelerator and then three years later, you’ve got 25, we would count that as massive progress because it means that you’re building traction at that community level. So funds raised jobs created profit generated by the new startups, those are, I think, really great and traditional metrics to look at. But helping match metrics with the early stage ecosystem development is important, too, right? You’re not going to have maybe 7 million raised in capital out of the companies in the first incubator ever, or maybe one company does that. And that’s great. But ultimately, you may not see that happen right away. But to match that metric with wherever you’re starting out, if you’re just trying to get folks to pivot, a small business idea, let’s say into a scalable tech startup in a week long, you know, startup bootcamp that’s going to have different and should have more than grounded metrics, then what you want in your accelerator program, after you’ve been doing this community building for three years, let’s say,

26:57

could you talk about, you know, kind of changing gears a little bit here? Where can someone find resources as a community leader or entrepreneur for supporting rural startups? You mentioned a book earlier startup communities? What other resources at quarry or or, or more broadly, Do you often recommend?

27:14

Yeah, I mean, like I mentioned, doing that book on Brad Feld, I mean, Hathaway book is, is, I think, a great tool for learning and for rural ecosystem builders to really get that perspective. I also, you know, selfishly would say what we’re doing at Korea is really partnering with folks to help navigate How can they build this startup community? What do they need to do? Who are the partners, where’s the funding? So we do a lot of that I also point people to the resources from the Kauffman Foundation, I think they are doing some really innovative work and are supporting entrepreneurs in you know, the heartland in rural areas where I think it’s really needed most. So I also think that as much as I mentioned before, you’ve got to get the actors and then governments and the stakeholders to really understand and put the needs of the entrepreneurs, front and center. And assuming you can do that, I think that governments actually a great source of support for entrepreneurs and for ecosystem builders. So if you know how to navigate those complexities of federal funding, SBR process can be great for non dilutive funding, though it can be challenging. There’s also a lot of programs through the Economic Development Administration, we support communities to apply for the build to scale program, which helps you really get that first infusion of capital to build out a scalable tech startup ecosystem. There’s also the USDA rise grant, which was just announced, which provides funding for tech innovation, entrepreneurship, even building physical infrastructure, building the incubator space that you may need. So I suggest you know, folks stay in touch and tuned into what federal funding opportunities are coming down the pike that Kauffman Foundation that Cory I mean, I would say the content that Joel are producing to at Great North ventures could be fantastic for people in your region. So I think it’s important, yeah, to take the national level, understand what’s happening at sort of that layer of the entrepreneurial vision and possibility in this country. But also what’s happening at your community level are they’re great people producing events and content and trying to make connections. And they would love to have more people at those events and reading their blogs and showing up and so finding whatever is in your area, but also tuning into some of those natural national resources. I also just really appreciate the work, though it may not be a resource they bring a lot of, I think thought leadership to this work is village capital and rise in the rest. So those are two that I kind of like to look to as well for what are they thinking what are they saying what are the frameworks they’re putting out? And, you know, how does that look and compare to the work that we’re trying to do in building these ecosystems in rural Specifically,

30:01

thanks so much for coming on the podcast, Molly, I usually close out with the same question every time. And that’s to ask you who is someone, or a team or a startup, or in your case, it might be an organization, but someone who’s flying under the radar, maybe people haven’t really heard about them. But that’s really executing, that people should be paying attention to.

30:24

I, it’s funny, I would take a wide approach to this question and say that every rural community that we work with is in many ways flying under the radar, right and should be looked at as a really, you know, interesting place and a inviting place to invest. And to just understand more and more about what startups are there that tech startups are actually viable and are happening and are being created in these rural communities. And I definitely think I would be remiss not to mention Red Wing, Red Wing, Minnesota being a place that we work and partner with that community. And though it’s not exactly under the radar, because one of their startups was on Shark Tank, actually. And I was just, you know, learning a little bit more about her story, and was really proud of just the way that she has built this company with her brother from the ground up and ultimately got an offer from the sharks and turned it down and is just crushing it otherwise with profit. So I love to see those kinds of things. It’s not under the radar. But I think there’s lots of other entrepreneurs in Red Wing and being served by Red Wing ignite, the one entrepreneur first collaborative that they have there, which I think is just really cool. It’s another model, like we talked about building density, that’s a great model, because they have regional collaboration, they’ve got 11 different counties within southeastern Minnesota, all working together to try to build up that, you know, pipeline of rural tech startups and amplifying those entrepreneurs. So another one I think is really cool. You guys may know is doc labs, this robot that will help people be better at basketball, I just love I mean, those kinds of stories of people having problems that really personally affected them, but then figuring out well, how can we how can we solve this because that’s a real pain point for you know, actual people in this world and solving that and going after that, I think is just, that’s the heart of what entrepreneurial ism is. It’s identifying what needs to exist in the world that doesn’t, and how can I go out there and build it? So seeing that happen in places like Red Wing in places like Wilson, North Carolina and Durango, Colorado, I mean, to me, it’s, it’s that’s the stories that need to be told those are the underdogs that we need to be uplifting. Those are the people flying under the radar that I could talk about all day, because I just think it’s really exciting that we have so much more as this as a country to give in terms of entrepreneurship in terms of innovation than just what we see in these five major metro areas.

32:57

What a great summation to that’s what it’s all about identifying problems people have and fixing them for him. That’s fantastic. Again, thanks so much for joining us on the podcast today. We’ll catch up with you later. Yeah, thanks me. So fun.

April Newsletter

June Newsletter

Demystifying Startup HR

Head of Finance & Fund Administration- Venture Capital Firm (Remote)

Demystifying Startup HR

3 Portfolio Companies Make Inc. 5000 + Quicklly & Instacart Expand

iraLogix closes $22M + Branch expands with Uber

iraLogix closes $22M Series C

Flywheel lands Gates Foundation grant

Venture Capital Analyst

Orazio Buzza, Founder and CEO of Fooda – on Episode 13, “Execution is King”

$40M Fund II Raised!

Eric Martell, Founder of Pear Commerce: Episode 13, Execution is King

Great North Ventures Raises $40 Million Fund II

Investment Thesis: Fund II Strategy

Investment Theme: Community-Driven Applications

Investment Theme: Digital Transformation Through AI

Investment Theme: Solving Labor Problems

Trends in the Gig Economy + Work in the Metaverse

Portfolio raises $125M + talking fundraising with Branch CEO

Omnia Fishing closes $4M round, joins Great North portfolio!

Atif Siddiqi, Founder/CEO of Branch: Episode 11, Execution is King

Michael Martocci, CEO and Founder of SwagUp: Episode 10, Execution is King

Yardstik new to portfolio, closes $8M Series A

First venture studio startup comes out of stealth!

Insights for founders from a data guru, + FactoryFix raises a Series A!

Una Fox: Episode 9, Execution is King

Start With a Mobile App, Not a Website

2ndKitchen acquired by SoftBank-backed REEF + advice from an early Googler

Joe Sriver, 4giving: Episode 8, Execution is King

2ndKitchen Acquired by REEF

Venture studio startup jobs + advice for founders from founders

Best Advice from the Great North Annual Event: Episode 7, Execution is King

Newsletter: Do you fit our investing themes?

Jonathan Treble, PrintWithMe: Episode 6, Execution is King

Anna Mason, Revolution: Episode 5, Execution is King

Mynul Khan, FieldNation: Episode 4, Execution is King

Nick Moran, New Stack Ventures: Episode 3, Execution is King

Molly Pyle, Center on Rural Innovation (CORI): Episode 2, Execution is King

Justin Kaufenberg, Rally Ventures: Execution is King Episode 1

Newsletter: “Podcast Launched: Execution is King!”

“Execution is King” – the Great North Ventures Podcast

Newsletter: Fund II is open for business!

Unlocking the Potential of Anonymized Commercial Real Estate (CRE) Data

Fund II is open for Business!

Mike Schulte Promoted to Venture Partner

New Name + New Venture Studio

Great North Launches Startup Studio

We Don’t Need No [full-time MBA] Education

How the University of Minnesota is Embracing Startup Culture

Top Stories of 2020, iraLogix, and LaunchMN Calls for Mentors

Building Capacity for Innovation

Seizing Opportunity in a Recession, Allergy Amulet, and Twin Cities Startup Week

Recessionary times, a record-setting IPO, and Minnesota’s Resilient Startups

Minnesota's Resilient Startups

July 4th, Equitable American Dream-ing, and Robots Diagnosing COVID

Jumpstart, the Startup School, and Branch Wins a Webby!

COVID-19 Trends, the Great North response, and our Founders Survey

Giving in the Time of Coronavirus

COVID-19 Resources for Startups, State-by-State

COVID-19, the CARES Act, and startups stepping up

New Business Preservation Act

Digital Future Boardroom, PartySlate, and The Lean Startup School

Great North Labs’s Startup Summit 2020

Great North Labs's Startup Summit 2020

World Economic Forum, NoiseAware, and the Startup School reboot

Great North Labs at the World Economic Forum 2020 in Davos

Top 5 Stories of 2019

Taking the Founders Pledge, Inhabitr, and gBETA Pitch Night

Founders Pledge: Support the Organizations that Support You

BETA Showcase, Greater MN, and Launch MN comes to St. Cloud

7 Places to Spot Us at Startup Week

The Greater MN Meetup, Parallax, and Exponential Medicine

Greater MN at the big show, Neela Mollgaard heads Launch MN, and Misty’s roadtrip.

Talking VC, tech kids, and Forge North’s Horizon

June: Great North Labs’s first fund raised!

May: Innovation Ecosystems, SingularityU Kickoff, and PrintWithMe

April: Minnebar Recap, ZenLord Pro, and Supporting Entrepreneurs

MinneBar 14 Recap

Dispatch and 2ndKitchen claim Tech Madness titles

Minnesota Innovation Collaborative

March: Minnebar, Hockey + Hustlers, and Innovation Workshops

Great North Labs at CES

Dec.-Jan.: Top Posts from 2018, pepr, Glowe, and Misty Robotics

Carried Interest: Top Posts from 2018

Oct.-Nov.: Singularity University, Exponential Tech, and the State of Innovation

Digital Transformation Summit, July 25th in Minneapolis

June: Silicon Lakes, FactoryFix, and the Digital Transformation Summit

Putting the “Silicon” in Silicon Lakes

Digital Manufacturing and Logistics

May: Team Genius, IoT, and the Future of Everything

IoT 3.0

Healthcare Innovation

March: Exponential Tech, the “Goldilocks Zone”, and Minnebar 13

February: Team Expansion, Dispatch, and Startup School Events

Great North Labs Newsletter – December 2017

A Letter To My Younger Self

Great North Labs Newsletter

Great North Labs Featured on Tech.mn

Great North Labs Featured in St Cloud Times

Great North Labs – Featured on BizJournals.com