In this episode, Rob and Josef talk about some Twitter controversy over founder extravagances, and the difference between, say, personal chefs at work used for recruiting, vs. buying a used fishing boat with your profits. This is something we looked into in a piece Rob wrote on BuiltIn, “The Weird and Wonderful Things Midwest Founders Do After They’ve Had a Big Exit“

Jonathan Treble joins and talks about his path from Wharton grad to startup employee to Founder/CEO of PrintWithMe.

He also talks about building his company, and practical milestones he set. He also has valuable advice for founders:

“Optimize for control over valuation” – when negotiating at early stages.

“Validate with the smallest team that you can” – because, really, more money means more problems.

He also talks about team building, which is something Jonathan excels at. They use the “Culture Index” to guarantee culture fit, which is incredibly important. He talks mistakes, onboarding, and recommends two books that created his own foundation for recruiting:

“Who” by Geoff Smart and “Recruit Rockstars” by Jeff Hyman

Who does Jonathan see executing? Orazio Buzza of Fooda, Inc.

Transcript:

00:00

Welcome to the execution is king podcast. Today we have Jonathan treble founder and CEO of print with me, along with my co host, Rob Weber, managing partner at Great North ventures. Welcome to the podcast, Jonathan.

00:16

Thank you. Happy to be here. Thanks for having me.

00:19

So Jonathan, I know we first met a little over a couple years ago, I believe, and you were kind of busy starting to really scale your business print with me. Maybe for starters, could you maybe introduce us to how you got to that position, you know, whether it be where you went to school, maybe some of the influences you had from a career standpoint, which sort of led you to print with me?

00:42

Definitely. So I started my business journey in undergrad, my undergraduate program was at the Wharton School, I majored in finance. But generally, it was a very well rounded business program. And I went into business school because I knew that I wanted to get involved in business in some way. Even back in high school, I had started a couple companies in high school. And I had the entrepreneurial edge, I think that comes from my parents, and particularly my father got me started with an eBay trading assistant store in high school. And it was so much fun to build the business and see that have some modest success in high school. I went to Wharton, I studied four years of business Warden is very much a finance school and breeding grounds for wall street and specialty services, firms, consulting firms, etc. And so that flavor of education was a little too formal for me. I realized at the time, I was not really going to use a lot of the finance in my career, although it was great background knowledge. And at even at the same time, in college, I had a couple of side businesses going right after college, I joined a startup in New York City that was founded by somebody I had helped in an internship. And that was my first foray into startup land. I immediately loved it and understood why I am meant for startups, right. And that is just the pace, building something out of nothing. The ambiguity that I like working inside of, and I took that job in New York City, and they haven’t quickly moved to Chicago. And the the story there just kind of all worked out well, for me, I guess is that this New York company took a round of investment from light bank, which was the newly named venture organization founded by Eric lefkofsky. And Brad keywell, who are known to be among the best serial entrepreneurs in the whole country, certainly, probably the top and Chicago, because they’ve, they’ve taken public, at least four companies I can think of, and now we’re working on one or two unicorns that are still private. They’re just incredible entrepreneurs. And when I heard that they invested in in my friend startup and that I could join, and then they needed somebody to go to Chicago and liaise with them. I was like, Yeah, that’ll be me, for sure. So I read jumped at that opportunity, moved to Chicago for that, and ended up with that startup for about a year wasn’t really gaining traction, I switched over to another light bank, back startup, and then even another did some consulting. And after about three years, I wanted to try something a bit different. I wanted to get the big startup experience. And what I mean by that is like a larger at scale startup. So I applied for a job at grub hub, I was given the position, I joined as a project manager on the tech team, slash business analysts. So I was essentially in charge of the development work for five engineers. And these engineers were pretty senior, like much, much more accomplished and experienced and knowledgeable than the more junior engineers I was working with at startup land. And I got to really learn how software is delivered at scale grub up at the time was, I mean, calling a startup is definitely an accurate in 2013. It was way along in his journey and actually getting ready for an IPO already. But it still had the startup feel. And so I joined this, this tech organization, the tech org at the time was probably 50 to 100 people. And I was one project manager among many over a certain team. And that was great. His big company experience I guess, to learn how to work on a team within a big company and I was my job as the business analyst there was to liaise with other departments in the company and help build software to meet business needs. And so that actually gave me a lot of insight into other facets of grub up. So other departments, ranging from marketing, to finance to customer support operations, I got to be the person to kind of liaise with a lot of those departments and help them solve problems with software. So I think that that year that I spent doing that full time was among the more important learning opportunities in my then career, because I got to see what a startup would look like, at larger scale. And kind of what, as a founder, a future founder, I should be keeping in mind kind of like setting as a North Star for my own venture down the road. So at this time, I was about 2526, I was dabbling with a couple other business ideas, startup ideas, I even funded myself, I bootstrapped, that a couple people would help write code for me for a couple of these ideas, and we put them out there and we tried to get some traction, and neither of them really took off. It was there were interesting ideas, for sure. But they lacked some, some point of traction. And

06:20

I suppose during all that time at grubhub, you know, building products to meet business needs, you kind of built may have built up a backlog of these ideas to try out. It sounds like you tried out more than a couple of them.

06:33

Yeah, Funny enough, the ideas I was trying out, didn’t really come from grubhub, I did get a lot of exposure to different parts of grubhub. But the types of problems we’re solving at that scale, weren’t all that. Well, I’ll say some of them were innovative. But a lot of them were just scaling systems. Like, for example, I had, I had the good fortune of being the business analyst who is revamping our accounting system and, like re building out the business logic for like, what activities wound up in which ledger accounts which is mind numbing, but good experience for I think, just just to have that a little bit of that background. And don’t get me wrong, we worked on some innovative things as well. And I was actually I think I, I was involved in some patent application with one of the founders because we came up with a way to track delivery times better through through an interesting system. But you know, by and large, most of my job was was just the nuts and bolts of, of scaling systems, which in itself is interesting stuff. I liked it. It’s intellectually challenging, but it was not exposing me to like a very wide range of ideas. So these other ideas, were just things that I was inspired by in day to day life. And one was like a meetup app, like a spontaneous meetup app, because at the time there was not in this is 2013 meetup.com was very, like planned. And so the a few companies have tried this I I would later discover and that the issue with traction is, I mean, it’s, you know, how do you build a network effect, it’s so hard to acquire those initial users you need. You need like person liquidity, you need a lot of people to be wanting to meet up at once. So it’s, it’s really tough, and then monetizing it as a whole nother very challenging endeavor for that type of app. So this is all setting the stage for how I ended up at print with me, right? So around 2014 I think it was early in the year, I needed to print concert tickets for a concert, right downtown in Chicago. And it was kind of a last minute decision to go to this concert. So it was the weekend. I couldn’t print the tickets at work. I realized I needed to print them somewhere else. And I didn’t own a printer. And I remember having to get into at the time, I think was a cab because early days, I mean Uber Lyft. We’re not quite there yet. And I, I drove about a mile away to a FedEx Office, I printed those tickets, I drove back in the cab. And the whole thing probably cost like 25 bucks between the cab fare and then FedEx Office rates for printing. Just thought, Wow, what an expensive thing to do. Certainly I could have bought a printer at that point and realize I save money in the long run. But I was also moving apartments somewhat frequently. I was in my mid 20s I was embracing the sharing economy. I was thinking, you know, why do I want to own more stuff? And I bet I figured a lot of my peers and people in my cohort felt the same way. And so the idea kind of struck for printing kiosks and it was an interesting idea. It was a kind of like a wacky idea. like okay, who would actually put printers in public places right like It sounds like that’s maybe problematic, like, I could foresee many ways that that would break and how it’d be tough to manage. But the idea really kind of sat with me. And for a few months, I kind of pushed it off. And I was like, I don’t know if this is a great business, and I was working on the other ideas at the time. And then one day, in the middle of the summer, I kind of just had this this moment where I was like, You know what, that idea is still bugging me. And it actually I, I could use that myself. And I bet a lot of people could, and why not just try to build it. So I just decided to go for it, stop the other projects work on this as my key focus. And that’s how I ended up starting it.

10:48

Yeah, there’s a lot of good useful lessons and kind of your your origin, how you got print with me off the ground, I think a couple of the things that really resonate with me is just overall, I think, when people see successful founders, they often think that, you know, that they’re, they don’t think of all the background work that went into sort of honing your skills, and they’re just hearing your stories a lot like my own where it was like, I wouldn’t necessarily call them failures. But like, there were a lot of projects that I was gonna tinkering with, you know, before we had kind of our breakout success, which, you know, went on. And I think that’s a really common theme with a lot of entrepreneurs. And I’d say, the other ingredient there was to just working at seeing another company at scale that was, you know, previously a startup, be able to learn from the kind of execution, especially in like a product or product engineering type of team, we’re actually working on the product. And, you know, ideally, probably some exposure proximity to one of the founders, like I think, you know, that is that can be so powerful for people who want to know, they want to be a founder, but they don’t know how to get there. I have a lot of young people who reach out and say, hey, how do I do what you did? How do I become a founder, I think there’s, there’s these like two logical, and you should have both of them. I never had the sort of bigger company experience. But I think that’s like to be able to see the, you know, the startup at scale, alongside your own tinkering projects, that’s got to be super powerful, right?

12:13

Yeah, it was definitely powerful is the best education I could have ever wanted or gotten better than a definitely better than like an MBA or an advanced degree. And I actually think you’re right grub hub. That year was very important. It gave me the Northstar for how a scaled business or scaling business needs to look like and how the different departments interact, and how technology can support all that. Very important lessons that I still have with me this day. And a network of people that I still keep in touch with this day, and that have helped out and consulted with me, you know, subject matter experts. But I’d even say going back before grubhub. So there’s three years that I was in startup land, at early stage startups that were still trying to figure out product market fit, and building product. So I was, I started as like a sales rep in the first job for a year. And I switched to Product Manager at the next startup. And I did that for two years, about two years. And those experiences were almost just as valuable. In fact, arguably, maybe more. So I got to see these founders, these early founders, in their process of tinkering and trying to make a product that was in demand and viable. And that was just such an incredible learning experience. And I got to do it on somebody else’s watch or like, on their dime, in a way, right, they were paying my salary, I didn’t have that much risk in it. Certainly I was like earning under market because it was a startup, but I was learning a ton. And so that the combination of all those experiences was super helpful. So that when I went to start print with me, I already had a lay of the land of like, financing fundraising, what, you know, common pitfalls that some of those founders have fallen into with, whether that’s building their product, or dealing with fundraising, and investors, right? So it was four years of incredible learning, you know, from the startup land all the way through grub hub. And I would encourage anybody who wants to eventually become a founder, if you haven’t already to get some sort of experience as an employee at a smaller firm. Right? As as early as you can. I would encourage that. And, yeah, I’ve taken a lot of that with me even to this day.

14:36

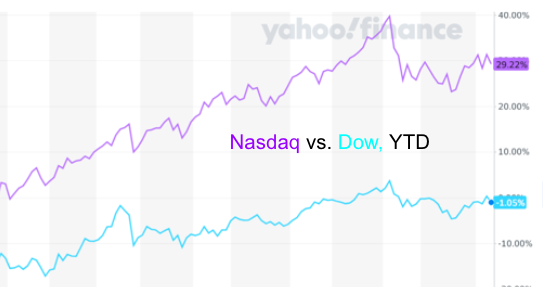

Yeah, so it’s interesting, Jonathan, I remember if I think back to when we first met, one of the things that really stood out to me was just kind of your, your sort of more pragmatic view on raising capital. If we go a little bit deeper down that path. It certainly like immediately just like kind of clicked for me as a founder who bootstrapped a company you know, some some level of success and I think there’s just like Eat this echo chamber and venture capital and startup laying that it’s sort of like, you get on the train, and you just raise round after round. And it’s sort of like the tech media just celebrates, you know, these markups and these more dilution and more dilution. And I think it’s almost unhealthy in a way of, of, you know, the way the VC industry kind of like, almost like, perpetuates this sort of like myth about building a company. And I think I’ve really respected Can you talk a little bit more about your sort of mindset with how you funded the business, getting it going, and now scaling it?

15:34

Yeah, happy to I, I’m very passionate about this topic. As an early employee, pre IPO employee at grubhub, I was given some stock options. So I’ll start there. And that was, I think that was great that the founders still allowed early employees, I was like, employee 500, something. I was definitely not early, but they pre IPO, every employee still had a grant of options. And a year later, I was there on IPO day, I was still full time there. We all were in the money essentially. Right. And, and in a big way, I think the IPO popped. And incredibly the first day, certainly a lot of my peers who had been there many years were way, way better off than I was. But this was a modest, you know, a modest gain for me early in my career. And it is true what they say that when a when a tech darling in a community IPOs or exits and, and it’s a good exit, a meaningful one a big one, a lot, it creates a whole class of new founders, right. And they’re, I know, several who’ve gone on and founded new things after that, and, and so the liquidity was great. Again, I don’t want to overstate this, it was very modest. But for me, it was the working capital for bootstrapping print with me for the first six months, before I started raising some funds from friends, I’ll start with that, I think that’s important to reiterate, like being an early employee, getting those options can actually be life, life altering, I won’t say changing. And then I’d say my philosophy in the early days of Chrome with me, so like your, the first two years was to just raise enough funding to reach certain milestones, right, just enough to kind of keep validating that this is indeed a good business. Because when I first started with me, I went in with eyes very wide open, that this may not work out, this has a high likelihood of failing, actually, and I have no idea if consumers will actually pick up on this. So I said, I told myself, I was like, I’m gonna give this three months, if I don’t see any traction, after putting alpha test printers in a few public places, I’m just cutting the cord and moving on to my next idea, right, I was 26, I had nothing to lose, which is another critical part of being a founder, you really need to be be okay to like not earn any money, or it’s better if you have less to lose or lower lifestyle at that point. And I certainly had a pretty humble lifestyle at that point. And so I just figured it I bootstrapped for four or five months, just paying the developers on my pocket, I’m still working part time at grub hub, right? I luckily, they, they were able to reduce my hours to like 20 hours, which gave me enough money to pay my bills, and invest some of that money into into print with me. And there came a time where we had bought a bunch of printers, we wanted to increase our, our velocity for developers. So I wanted to hire a third developer contractor at the time. And I was like, no, what I should raise some money, I could really use some more more funding here. So I started going to friends first, and a good friend of mine from study abroad, wrote the first check in like December that year, so about five months in. And then another acquaintance from the light bank portfolio wrote another check after that, and another college friend wrote one of my former boss So in the first six months of fundraising, I just raised 50 grand from, you know, on a convertible note, and it was like such a shoddy convertible note that probably had tons of mistakes in it. But we ended up you know, converting that into equity with the first price round about a year and a half later, but that was it 50 grand to just fund more development and more printers. And again, bring me to a milestone where I would decide whether it was gaining enough traction to continue even further, you know, that end up being not very diluted at all, but enough capital how we could prove that. And then, at the same time, I was getting great mentorship from one person in particular comes to mind rasio bouza, who’s the founder and CEO of fouda Buta Inc. in Chicago, they do pop up restaurants in, typically office buildings. And they’ve grown an incredible business. And he’s a light bank veteran as helped two or three of the light band companies go public. And he was telling me early on throughout my early days tinkering with print with me, he was saying, you know, I wouldn’t raise that much money. I try to bootstrap as much as you can retain ownership. Right. And, you know, he didn’t think the print with me was a business that was really set up for venture rounds of funding, like ABCD, etc. And I think he was probably right. And I’m happy that I I raised in dribs and drabs slowly, because I still retain majority ownership today, and majority control. Importantly, and I could have easily gone away had I been enamored with the venture cycle of raising so many rounds, and you know, giving up more board seats losing control, right? That stuff is scary. I mean, you know, I’ll jump forward a little bit to when we did raise our first price round, it was August 2016, that we got the first term sheet. And, to his credit, Jeff meters, network ventures, was one of the only VCs in Chicago that would take a deep look at permits me bear with me scared off most other VC is what a printing company right? As it as I totally understand it would, right. And he got in the numbers, our traction saw, saw the growing revenue that each kiosk was making, like, wow, this is actually a good business, great margins. at scale, it can be a meaningful business, a decent size, exit, you know, medium to large. And he said, you know, I’ll do a term sheet. So we did that. And thankfully, right I, and I’m saying this to help maybe other founders that end up in this position. And, Robin, I know you’re a VC now, so I hope you hope you don’t, don’t mind me like giving some advice the other side of the table, but you’ve been on both sides. So I’m sure you don’t mind. Like I got great mentorship from two of these people that I looked up to when I was reviewing that term sheet. And both rasio and Mike Evans, a co founder of grub hub, when we were reviewing it together, they were like, you, you cannot give up a third board seat right now, right? Like the term sheet initially said, One investor board seat, my board seat, and then an independent third. And this was like a pre seed round. And they were like, No, no, no, you can’t do that. That’s crazy pants. So of course, I pushed back on that. And they, their advice was optimized for control over valuation. So I gave up the point on valuation, it was still a decent valuation for where we were at the time. And I but I was firm on retaining two out of three board seats. And to this day, I have so at I mean, I tell you, five years later, if I had if I hadn’t had that advice, or I’d gone the other way on that I would have many more sleepless nights because, you know, there’s there’s another group of people a board that could technically asked you, whenever, you know, they think that’s that’s the right call. And that can happen and does happen a lot of founders. So you know, I’m very happy for that for that advice. Now on raising capital in dribs and drabs, oh, I’ll continue, I raised that round, it was just 500k in new funding, all the previous notes converted in for equity, the post post money was like 3.1 on that. And then that was enough, again, to kind of validate that I could build an early sales team, we’d continue to get traction, some sales efficiency, get ready for maybe an A, well, we didn’t hit quite all those metrics. In the first year I struggled with hiring I made some poor hiring choices. And nevertheless, we were still growing, we actually tripled that year, but it wasn’t like what I wanted it to be, we’re able to go raise a seed two, which is definitely a thing now. And we’re it was an up around, I think,

24:20

an 8 million posts. And, and that, you know, was another I think, in fresh capital that was another like 900 at the time. And I was like, Alright, well, this might all be all we need to really get a sales team in place that can harm and, and prove the model and that ended up being true, I only needed that. It gave me another year and a half of burn, right? hiring and getting getting the team more efficient. And then we we reached profitability a couple years down the road and didn’t really need to raise again and You know, certainly it’s slower. It’s a slower path. It’s not for everybody. It’s not for every business, right? I, you know, the venture path makes sense for a lot of businesses, but not for my business, and certainly not at the time.

25:13

So when you’re talking about like raising, and like setting these milestones, you also talked about, like, kind of like a friends and family round going to people, you know, so were you matching up? Were you like setting the milestone first, figuring out what you needed, and then setting the amount? Or were you kind of gauging how much capital you can expect to raise, and then readjusting what milestones you can hit with that capital expectation?

25:41

Yeah, that’s a great question. I’m not even sure I can remember exactly what my thought process was. Go back now, five, four years, you know, I think, I think it was, well,

25:52

maybe just knowing what you know, now. Like, maybe if you can’t remember, like, instead of the chicken and egg quandary we could get into right now, if you had to devise somebody, what what would you tell them?

26:04

Yeah, I think I would advise to go the former route that you described, which is, pick your milestones like, what do you want to validate with, with your funding and figure out what you need? Yeah, figure out, like, what your use of funds will be? Like, do you really need 10 sales reps? Or can you validate with three? Right? All right, well, three is a lot cheaper than hiring 10 sales reps, right? Do you need five engineers or can you get by with to really try to i, in my opinion, validate with a small team as possible, because then you don’t have to raise as much at such a low valuation and dilute as much. But also, like, more money, more problems, right, you raise a $3 million pre seed, you’re going to have a ton of stress trying to hire up to to meet like, the expected burn on that in like six months, you’re, you’re gonna make hiring mistakes, these are gonna feel time pressure, you know, go slow in those early days. Unless, of course, you there are certainly exceptions where like, if you’re really on to something that can be a massive market opportunity, like 10s of billions and like, you know, someone who’s gonna copy right away, or somebody else is going to, or there already are competitors, you gotta go fast, right? And that’s, that’s where raising a lot of money and trying to blitzscale make sense where it’s a winner takes all are most market. And if you don’t act quickly, a competitor will, will take it right. I think that’s where, where you have to, but for a business like mine, where I didn’t see any competitors coming after us. And still, to this day, there really aren’t any, like, I didn’t have that time pressure.

27:53

It’s so interesting. And I just love I couldn’t agree more. It’s interesting. So on episode four, we had my new con from Twin Cities bass field nation, which is huge breakout success that the story isn’t very well known because we did this sort of friends and family round with my new Alcon he was sort of my brother’s computer science lab partner at St. Cloud state and central Minnesota. You know, he skipped all the subsequent funding rounds, no seed round, no way around, no, no, maybe not even a B round. And then he raised like 30 million after bootstrapping for seven years. And the weird thing about my news story, in his category, there were several direct competitors that raised far more money and ended up just flaming out. And actually one case, he acquired the company, it was just like, this is why we have the execution is king podcast, not be blitzscale and raise the most money you can podcast, because it very much it speaks exactly to the core of our beliefs, which is, you know, it really execution matters the most. And I think it even matters and even in cases where there are competitors, multiple competitors, even some with a lot more capital, you know, stronger execution with the right strategy will kind of Trump the capital all day long, right? I believe that it definitely is a little more nerve wracking as a founder, when you start, you know, having a more direct competitive pressure and in there, you know, maybe categories where there, there’s just a lot more capital flowing into it. But even then, like, I think my new is a great example. So I think that’s probably why like, this sort of mindset you had is very much aligned with my own, you know, in terms of just capital efficiency. And I think there’s also this being cognizant of the overall competitive landscape like you described, like that. It’s just so important. So I know, obviously, you know, if we fast forward to today, you know, growing the company is gone from like, will the idea work? You know, scaling and scaling, of course, means expanding the team. Can you talk a little bit about, you know, some of your lessons learned in terms of recruiting and building up your team and maybe we can dive into that for the last part of the podcast here?

29:56

Oh, absolutely. Yep. And I mentioned it earlier, but I made a bunch of hiring Mistakes after my first like large round of raising and which was 500k. And so it was it was actually the investor, the lead investor Jeff gave me a book on recruiting after that he was like, you should probably read this book. I was like, Okay, great. So I read it. And it was cool by Jeff smart. And that’s like one of the classic recruiting books out there. And about a year later, I picked up another book by Jeff Hyman called recruit Rockstar. So those two books have formed the backbone of our recruiting process, I’ve just taken their processes and kind of melded them together in a way that I think makes sense. And I hate

30:41

to interrupt yet, but I don’t want to get too far away from this. You dangle that out there. And I just got to ask without naming any names. What was your worst recruiting mistake?

30:52

Worst recruiting mistake? I think so hiring a couple of people at the same time who had fantastic like results on paper in sales roles, but were toxic for culture. So really, like just looking out for themselves to money motivated? Yeah, like all about themselves and not not willing to care about the team or the company. So that was so so I shortcutted the the interview process with those, those two people and it was disastrous for the culture, right, a couple other good people left because they were there and, you know, so that set me back a few months in the middle in the middle of this whole journey. But that was a lesson I you know, definitely learned and avoided that mistake after that. But yeah, that’s a it’s a great question. I made plenty of mistakes, I think I’ve made every recruiting mistake you could possibly make. But that one stands out as the worst in terms of impact on the company. And so I started getting building a process with these books. And and also like, you just build muscle for this right over time, you you get more confident in recruiting and interviewing and, you know, the imposter syndrome goes away a year into it maybe of recruiting and, and so I’ve learned a lot and even even from Jeff hymens podcast recruit rockstars, where he takes he brings on entrepreneurs, and they talk about recruiting, and lessons learned. I mean, I’ve learned so much from there, too. So now I feel like we have a really good process. But it’s so important. Nope, it was a lesson for me. Pretty pretty early on in the entrepreneur journey that I can’t do everything right, I, I find myself to be pretty bright, and like, adept at many different things. I like back in a year into starting print with me. I was like, I had my hands on everything, right? I was leading the tech development, I was leading the operational side I was selling I was like, marketing, I was doing everything. And I loved it, because I like doing a lot of different things. But at a certain point can’t can’t just scale like that. Right? And, and that, and I thought it would be kind of easy to hire people and just have them do the roles. But no, you know, you got to find great people for each role. And that was like, a learning opportunity for me, right? I think it was 28 when we started trying to hire people and at scale, and you know, and so that like learning how to identify strong talent for a role. Also make sure that the talent matches your culture that you’re trying to build for the company. Understanding like the difference between an entrepreneurial employee and somebody who works at a large company that needs so much structure and process around them and just gonna just flounder in your crazy mess of a startup, like, these are hard lessons learned. And I hope founders can avoid those mistakes by being very thoughtful about it and deliberate and listening to other founders who have gone through those same exact problems.

34:02

How do you how do you really like, ensure that they have the right personality? How do you how do you go through and like, I mean, it’s not like you give them like the Myers Briggs personality test are, you know, is it just a matter of the interview process and getting a lot of the right people on your team involved with talking to them?

34:22

Well, we do actually give a culture survey I’d call it which is a 10 minute questionnaire, and it’s called the culture index. And that is similar to Myers Briggs. It tells us at a high level, where an applicant falls on five or six different spectra of personality. So how driven they are right the competitive atop like seeking risk and autonomy, how socially our extroverted, introverted and in a way, how urgent they are versus more like methodical and Slow, and then how like detail oriented and conscientious they are, it’s been around for a while, it’s a derivative of like the five factor test, and like many people have written about it. And I use it religiously to this day. And so it is one data point among many in the interview process, and helps us get more comfortable with the idea of a person in a role and you figure out what archetypes and patterns you want for each role, and you try to make sure that your applicants match at least match majority of those spectra. So love that test that was introduced to me in 2018 by an investor who literally wrote a check for us to go get trained on it, like a five figure, check. He just wrote it. For me, it was like a gift. I was like, wow. But you know, that has been so game changing for the company that I’m sure he’s he’s, you know, it’s kind of like, he’s was protecting his investment, because he he probably also saw the hiring mistakes I was making. I was like, you gotta you got to go through this training, and use this test.

36:05

What What was the name of the test? I wrote down? culture index test. Is that the name of it?

36:11

Yeah, the culture index? Yep. Yeah, they’re, they’ve been around for, like 20 years. And there’s a great team at UT Dallas, I’m happy to put any founders that are interested in touch with with their leadership in Dallas. I’ll give my contact info after the show. But you know, it was transformative. I’m a junkie on that now. And it is, it’s really, it gives you a reference point that you you can’t even imagine for assessing candidates versus like the, the traits that you really need in a role. Now, that’s just one thing. You also have to test? Do they vibe with your culture? Like, if you’re trying to build a very Hustle, Hustle, Hustle culture? That’s like 70 hours, 80 hours a week? Well, are they willing to do that? Are they excited by that? Is that is that are they at a point in their career where they can do that, I was never trying to do that with all my employees. Since day one, I’ve expected just 40 hours a week, because we can get a lot done in 40 hours. And we we do I mean, I work I work a little bit more than that. But we’re, we’re still growing exponentially. You know it with a reasonable culture, they’re not not a crazy 7080 hour week culture. But you know, I realize some startups it’s, that’s, that’s what they want. And there’s good reason for it. In some cases.

37:31

I think that’s really interesting and kind of macro perspective, you know, our company’s scaled to 170 employees. And my brother Ryan, kind of, we were twin brothers, he ran kind of product engineering team and I, everything else kind of, for periods of time kind of rolled up to me. And so I think back to the way you evolved, your, your entrepreneur, your leadership style, sort of going out, studying the the areas, the best information available on certain processes, you knew you needed to scale your organization, and then bringing that into your business, on your own doing it on your own as an entrepreneur. And it goes something I remember, like in our sales organization, we got to several dozen people in our sales organization in my last company. And I think I read every, there’s all these different methods of selling, there’s like SPIN Selling solution, selling challenger sales, all these different methodologies. And I would just read up on all of them, I go, I think this would work best in our business. So we’re going to implement this. And then the next step was running a sales training workshop. And we’re creating case studies based on the book, you know, for this methodology that is completely built for our business. And it was like, and I thought it worked really well. There’s this sort of attention to detail on scaling, the organization, the onboarding that went into it. And, you know, even down to like an onboarding checklist for like, the first 30 days in an employee. There’s just I know, I was listening to your podcast interview on recruit rockstars. And you talked about, you know, the importance of strong onboarding, I think that’s something many startups, you know, really fail at, quite frankly, though, especially in the positions where, you know, you’re going to add a lot of staff. You know, it’s so critical. The early experience and employee has made me talk a little bit about like, you know, beyond recruiting like the onboarding experience, and some of the things you’ve learned as you guys have been building up the business.

39:21

Yeah, sure. So you, you hit the nail on the head. onboarding is very important. We’ve, I learned the hard way I had a couple people that I just kind of threw to the wolves and just said, Hey, can you go figure this stuff out, and that they didn’t last long, and that was my fault, right? But I learned some wisdom from Jeff in his book to take onboarding very seriously. So I started there a couple years back, I built an onboarding checklist of things that I think every employee approved with me should know. And you know, it’s it’s the nuts and bolts of like, systems, getting getting all your tech stuff on boarded obviously that’s going to be There, but also like, how we communicate what are our communication guidelines and standards? And what are our okrs? What does our OKR system look like we do objectives, key results, like the measure what matters, but we have every employee read the measure what matters book. So that’s part of the onboarding checklist. So we we try to be just as good about onboarding people into our culture as we do the nuts and bolts of the systems in the company and also like the knowledge for their specific domain or the role. Both of those things are very important. I we now have the good fortune of having two people in HR lead recruiter and then kind of an HR recruiter hybrid. And now that HR hybrid is onboarding people, and has a checklist and you know, he’s there, buddy, for for onboarding. But early on, it was all me, right? When you’re a 10 person company, you’re the founder, you’re doing everything. But like you said, Rob, I, I would read tons of books, I still, there’s there’s a bookshelf at our office in Chicago, where I dumped all my books before I moved to Denver last year, and it’s like, filled, it was probably 100 books on startups selling marketing, tech development. I mean, you name it, I think that’s another key point for aspiring founders is you have to be a voracious learner. You have to be humble enough to realize you, you don’t know everything yet. Which I, I’m not sure I was quite there at 26, I kind of learned the hard way. I need to level up a lot of skills in my late 20s. But you know, you really can if you’re open to learning and curious and you’re seeking it, you can find so much wisdom in any topic by just reading a book, and then bringing it to your business and saying, alright, this sounds great for my business. The next day, you incorporate it into your process, and you’re able to do that as a founder, right? Like there isn’t red tape, which is great. Your your employees might have whiplash if you’re doing that too much. So you can’t be a book of the week person but you got to, I think there’s a balance you can you could do it reasonably in a way that is beneficial for the org.

42:14

One of the other managing partners are great and adventures is Rob’s twin brother Ryan, co hosts other episodes. He is fantastic at producing book recommendations for me, I don’t know how many of his I have behind me on the shelf, but several and the last time I we were in person, I saw Rob and Rob recommended a book to me that I’m actually already currently reading a Clayton Christensen book. It was just fantastic. We are running out of time here though. I want to make sure we get in our last question. I like to ask every one of the guests on our podcast, this question focused, we’re focused on execution. And we like recognizing people who can do that it might not always be the flashiest people who are getting that recognition. So is there somebody, maybe it’s a team or a startup or a single person that’s really executing that maybe they’re flying under the radar, maybe they’re not maybe they’re deservedly, very popular, but someone that you’ve seen or startup that we should be paying attention to.

43:16

I’ll say I’m again, I always and I will always say this orazio bouza is probably the best operator I’ve ever met. And I’ve met a lot. And you know, just to give you a sense, so he he’s skilled three or four light band companies and food is is now an awesome success in Chicago. But I think he told me once and he wasn’t trying to brag, but he was just kind of explaining, like how he does budgeting. And he, he had set lot, you know, pretty ambitious projections for fouda in the early days when their fundraising and you know, some investors were passing on on a couple of his rounds, they just didn’t think it was for them. It wasn’t software enough. But then he would go back to them a year later. And he would show them the new projections. And they would see that he actually hit the ambitious projections. And they were like, no one ever does that. No one ever hits their startup rejections, but he actually does and I’ve learned a ton from him. He he, he’s probably the best. I mean, I can’t think of another so he is the best executer that I’ve ever met. So I’m happy to make an intro to try to help you guys get him on the podcast at some point.

44:30

Yeah, that’d be cool. Sounds great. Well, thanks a lot, Jonathan for joining us today. It’s been a pleasure.

44:35

pleasures all mine. I’ve really enjoyed the conversation. And yeah, good luck. Continuing with the podcast is a great idea.

44:41

Thanks.

Ryan and Josef talk about the Weber brothers’ long history, with Ryan tracking Mynul since they took classes together in college.

He talks about his journey as a first-generation immigrant who came from Bangladesh to St. Cloud, MN.

His biggest lesson for founders? “Never run out of cash.”

He shares how his “hobby” turned from Plan B into the only plan, and the importance of going all-in. Mynul is heads-down, and shares some great advice about maintaining and creating capability while discussing people, systems, and processes with Ryan.

Full Transcript Below:

00:00

Well, welcome, everyone. For those of you who don’t know me, I’m Bonnie spear McGrath. So thanks for joining me today. As an entrepreneur, there are few things I enjoy in life as much as hearing the story of other entrepreneurs. And today, I’m super excited because we’ve got two entrepreneurs in the house lined up for this session. Both are graduates of St. Cloud University. So I want to put in a big plug for St. Cloud University, because there’s a lot of social pressure on all those Ivy League colleges. And that’s not necessary. So and they’re both highly successful entrepreneurs, I first I’m going to introduce Ryan Weber, I met Ryan and his twin brother, Rob A few years ago, and I love their story. They’re both from St. Cloud, went to a cloud University, started their own kind of bootstrapped ad tech company, that they later grew to $70 million in sales and made a lot of money for their investors, which is always a good thing to do. And after doing that, they decided they wanted to start helping other entrepreneurs. And they they did a little bit of on their own. And then strat started Great North labs, which is where I met them and became an advisor and investor. And I’m super impressed with them, and their integrity and authenticity. So big plug for Great North labs. And one of the people that they helped early on was my new old con. So I’m super excited to invite my new look here. As I said, he did study at St. Cloud University, but he’s not from St. Cloud. He’s originally from Bangladesh, and came all the way here to study computer science, and later decided to stay and start field nation, his company that he founded any CEO of in 2008. And field nation matches company projects with freelance technicians. And that might sound very simple. And it’s a simple idea, but it’s a super successful private company in Minnesota in which we can be so proud of, they now have over 200 employees and offices in Minneapolis and Bangladesh. So that’s pretty cool. And I always say it’s good to hear the behind the scenes story about how something happened in terms of idea, and especially in terms of financing. So the conversation today between Ryan and Mike Newell will be very interesting, including any secret insights that they want to share that maybe Rob Weber, who’s also on the call doesn’t know yet. So welcome, gentlemen, thank you so much for being here today. Thanks for having us, Bonnie.

03:09

Yes, thanks, Bonnie. So my name is Ryan Weber here. We’ve known each other for over 20 years now. It’s it’s over half our adult over half of our life, not just our adult life, pretty much our entire adult life. But I’m really excited, longtime friend, and then a great classmate and advisor to current projects that were involved in, but maybe manual for the audience, you could start off by telling us a little bit about field nation and what you do.

03:36

So So fuel nation is the simplest way to explain it’s, it’s like Uber for Field Services, right? What we do is we connect businesses that need field service work done with with the technicians and engineers in the field, who have that skill set to get that work done. So think about, you know, all these retail stores, they need point of sales, to cabling to networking, all sorts of technology is getting deployed in retail, banking, QSR, quick serve restaurants, offices, and, you know, how do you how do you find this technicians? How do you deploy them? How do you know that they’re qualified? How do you manage the project, all of this is built into the Philadelphian platform, you know, we help businesses connect with the right technician in the right place, and help them manage the whole project from the start of the planning all the way to payment, back office management, all that kind of stuff. And when did you start field nation? I started field nation in 2008. That was March of 2008.

04:44

You know, I I think that people would love to hear a little bit about your background, being a you know, from Bangladesh originally and coming to St. Cloud State University to study. Could you talk a little bit about, you know, your background prior to field nation?

04:57

Yeah, so I’m originally from Bangladesh. I came here for college for my bachelor’s degree, I went to St. Cloud state. Usually when people hear that Bangladesh to St. Cloud, they immediately the follow up question is how you ended up in St. Cloud? And the answer is, when I was looking for colleges in the US, I learned that there is only one state that was at that time was at least offering in state tuition to foreign students from day one. So the taxpayers were, you know, graciously paying for part of the tuition for the foreign students. So as you can imagine, when you are Bangladesh’s, literally the other side of the of the of us, it’s literally 12 hours time difference. Growing up, I knew, you know, Hollywood and New York and LA, and never heard about St. Cloud, probably not even Minnesota, growing up, right. But then, as I was doing my research into what college, you know, and everything is expensive, you know, especially when you come from the other side of the world, a developing country. It’s like, okay, I can’t afford to go other places. And St. Cloud gives a great deal. And that was really the primary reason to come to St. Cloud sent out state. But very quickly, I just, I just loved everything. I just loved the school, the teachers, the community, the friendship, that right that I built, you know, my plan, or a general plan was, I’ll just do, you know, two semesters of, you know, general education courses and then go somewhere else. But then, you know, that never happened, I just really love this place and love the community love the school and decided to stay here. So right after college, what actually do you know, in the last semester of my college, I had the opportunity to do an internship with a startup called Ebro in St. Cloud. And, you know, I think I was probably the I don’t know, you know, fourth or fifth employee, you know, at a bureau. And that’s kind of where I really saw got the sense of, you know, what it takes to build and the fun of, you know, building and taking something to the market, the uncertainty. And I remember, the first day I went to Ebro, they were in this big, you know, quest building, there was no desks, chairs and stuff like that, you know, a couple of people are building product and stuff like that, I just love that. And so I never grew up thinking that I would have, you know, I would start my own business, but I just loved the whole process there. And, and then I started the first company, back in 2004, called technician marketplace. It’s really first version of field nation. I started that in 2004. And that company also grew fairly quickly. But I ran into cashflow problem, and had to shut it down. It took a year off, got married and promised my wife not to start another company, and that lasted a year. But of course, with our blessing started field nation in 2008. So that’s that’s the whole story, Ryan, all the way from Bangladesh to Phil nation.

08:31

In during this these early years, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced with starting a business?

08:37

You know, that for me, you know, the biggest challenge was that I didn’t have a network, right? Do you need a you need, you need to know people to start a business like, you know, people who can advise you people that you can actually hot, you know, not even higher, but say, Hey, would you work with me on this project. So my network coming from monitors, my network is really, really small. So that was, you know, that that was one of the biggest challenge, me being an immigrant had its own unique challenge, because I couldn’t just leave my full time job and do do this thing, because that’s that non meal wouldn’t be legal. So I always have to have a full time job, I would, you know, you know, do my eight to five, job. And then in my business, my entrepreneurship would be up part time after hour and weekend thing. So those are those are, you know, a few few challenges that I had to face. But, you know, I was I was very fortunate that the small network that I had, was very, very, very, very effective. You know, people like you, Ryan, I reached out to you when I first started my business, Phil nation, Rob and a small network of people that that I I grew up, you know, and the university was part of the company from the beginning.

10:06

Well, thanks for sharing a bit about the background. You know, I remember that those early years very well, a few years there later, I think we obviously we connected, interacted a little bit in computer science, I think a lot of computer science students do. I think at the time, we were very analytical, and kind of not a lot of social, social, not a lot of partying even though thing club seats sometimes gets that reputation. We were kind of the Nerds working in the labs. And so I think we got to know each other a lot more as we started to do business together. So flash forward to, you know, the beginning of field nation and the early years, what was different? What, what did you learn from your first experience? And how did you go about supporting and scaling the early years of field nation?

10:54

So so the, the biggest learning from the first one is that never run out of cash? Cash is really important. And that’s one area that I know, finance. And accounting is one area that I, I, I enjoy all parts of the business, finance and accounting was always a drag for me. And I always kind of wanted to avoid debt. And, and the biggest lesson is that, you know, cash is the lifeblood, and you run into that you’re dead. It was literally dead. And so that was the biggest lesson there. Scaling up, you know, starting field nation. I’ll tell you another another good lesson for me. When I had my first job, I never had the confidence to go all in with my business. It was, you know, partially, you know, I never saw people are on me to do do successful. I mean, of course, I saw you guys, but not in my family. Growing up, business wasn’t a thing that you do. It’s the the people who cannot have a job. Go start their own business. And so I grew up thinking, you know, you go for good, good employment. Something something safe. So, so starting the business was always like, it’s it’s sort of my hobby. My friends and family would tease as it’s my hobby, I mean, old doesn’t have anything else to do. So after hours and weekends, I just, you know, like you said, No, no partying, no, no life, no social life. And so what do you do you just go do your second job. But what happened in 2008, I was laid off from Ebro. And I remember that long path, long drive back from St. Cloud to Plymouth. I was living in Plymouth at that time. And I just felt rather than being scared, I was scared. But I felt more free. I felt like, great, there is no plan B anymore. It’s just plan A The only plan that just make filmnation happen. And it was just absolutely freeing experience. Because I was always trying to juggle the ball. And, you know, if, you know business, if it doesn’t work, it’s fine. I got another job. But the job that I have, that’s really important. Don’t screw it up. I’m going to need that. And when I when I got laid off, it was like, No, there’s, there’s a plan B, there’s just one plan. Let’s go go all in and make it happen. That was That was really good. That worked for me.

13:37

It’s really interesting. You talk about the kind of the culture a little bit of starting a business and going all in you know, we both were classmates in the Department of Computer Science at St. Cloud state and not I remember being called into the office by the department chair one day Sarnoff, that who you know, Dr. ramnath. And, you know, he asked, he asked me about my business, I thought he was calling in to reprimand me about something and then all of a sudden, I just decided, you know, I’m, I’m opening up, you know, I was going to talk about my my work, you know, in class and with faculty and everything changed, you know, at that point in it. And I remember when we met you were talking about we had been just a few years ahead of you and in building what was freeze calm and became native x. And, you know, it was those relationships. You know, in St. Cloud, we connected with a lecturer at Rob’s entrepreneurship class, Brian schoenborn who connected us with with somebody that had a lake home on his Lake, maybe you can share a little bit about the background. I guess, you know, I joined field nation a year before this gentleman as an advisor, you know, when you reached out to me, we hadn’t talked in a while. I didn’t really know what you were working on, but it was similar, like, maybe similar experience when I had with Sarnoff. You know, when you reached out to me, I was very interested and I was very much wanting to get involved in but until you opened up and kind of reached out I never knew you know really what you were up to and And even though I wasn’t invested in eat Bureau, you know that you talked about that. Maybe you could talk a little bit about that getting, you know, our angel investment and advising round together along with this gentleman and how that impacted your early years.

15:14

Yeah, Ron, I don’t know if I, if I told you this story. So I started the business in 2008. And a few months into into the business, I realized that I need not only I need some investment, I need some people who knows, who can tell me what I’m what, what I don’t know. And there was, there was a lot of things that I didn’t know. And, and literally, I started searching my LinkedIn at that time, I’m like, you know, I gotta find people that I know. It is a very, very small network, right? I just all of a sudden, I remember like, I do have a rich friend it, Ryan and Rob, let’s, let’s see, that’s out. Let’s ping them and see if they’ll, if they want to meet with me, and you were very gracious to meet with me, I remember us having lunch. And I was telling you, you know what I’m doing and stuff like that, and you’re giving me advice. And then we decided to stay in touch, because I think you liked something that I was doing. And we decided to stay in touch. And we I think we and since our kind of the first meeting outside the school, we probably talked probably for few months, maybe six months. And then I said, Look, I’m now ready to take some angel investment. Although my company didn’t have a lot of overhead I was I was always very resourceful in terms of doing stuff. So, you know, company was was was generating income and stuff like that. But a company was growing. Without a balance sheet. There’s no no no money in the balance sheet. But the company know the revenue and all that stuff started to flow. And it just made me really uncomfortable. I keep the nightmare of cash flow. from my previous company kept coming back. I said, I need to, I need to get some cash in the in the bank. And so I reached out to you and and you’re interested and quickly, you introduced me with young son, and young, I think you’re talking to young les comment in St. John’s, and he got interested in Phil nation, and you both decided to invest. That was my first investment into the company that was probably back in 2009. And at and you guys invested. And also you decided to stay involved with the company and time to time I’ll just call you up and say, here’s what I’m thinking. And I need people in this key roles and you are very, you know, gracious to, you know, help me connect with a lot of people and a lot of people are still with Phil nation, the people that you introduced me holidays.

18:05

Yeah, for everyone listening that, you know, young stone was a early connection that we made. Through his wall tap home near St. John’s young, young was a CEO of a tech company called Old technologies and lived in the same neighborhood was Steve Jobs. But we just were very fortunate that somebody in the community Brian shone bar and introduced us early on and, and young served as a mentor to Robin my business freeze calm. And when we began our family office, angel investing, we tried to model our behavior of, of young and young brought his friend in Pradeep madonn, who’s the third partner in our current venture fund, Great North lab. So we tried to when we Angel invested, we tried to lean in and provided any support and guidance, we could just like we were receiving from our Silicon Valley friends, thanks to Brian. But you know, those years, I remember, everything is just flashing back in front of me as you talk about, you know, this time period, because at the time, you know, we didn’t have a lot of active angel investors in many funds in Minnesota, if any that were doing this seed stage or or pre seed stage investing. And, you know, I think we were so you know, we’ve always looked for people that can execute, you know, and we love to find entrepreneurs like Mike Newell, you were working on your business and clearly had some traction yet, you know, you had to learn, you know, you had some hard, hard times in the early years and had to recover. But maybe, can you talk about how and I also remember, when we gave you the money, I thought you were going to spend it but it seemed like it never left your bank account. So that was maybe that gave you more confidence with scaling. But I’m really interested to hear more about when did you feel like things were really starting to hum and what were some of the major milestones, as you began growing after the after that period.

19:51

I don’t know if I can tell you one major milestone two kind of breakthrough moment for us but Well, I do have one aha that I always like to share. Yeah, which is, I was so naive, when I started, I thought, you know, you build a product and you do some Google AdWords and stuff like that, and all of a sudden things gonna just everybody start to sign up. And I was so naive, and and I waited and waited, you know, for for few months, and there was literally nothing. And I don’t know if this was a problem with a business model or, or what. And then I think towards the end of 2008, we had one bot customer sign up, just all by there is no sales for somebody signed up, one company signed up and did 20 work orders on our platform, our our platform is mostly work order driven, like somebody create a work order, and then they find a technician and deploy the technician in the field. That’s kind of how the system works. And, you know, by end of 2008, I waited six months and then end up to those and eight, somebody signed up, created 20, work orders found 20, technician nation, you know, distributed all over the nation. And I got so excited. I thought this is it, this is the moment that tells me that I’m on the right path. Now, looking back now, you know, last year, we did a million workorder, you can see that the scale of the company is very different. But there is nothing more meaningful to me than that first 20 workers that just just that was the lifeline for me, that just gave me this desperate validation that I needed. in those early days that it is the right, I’m working on the right problem. And people find value through my, through my product. And that then it was a question of, you know, the How do I figure out the sales and, and distribution and all that kind of stuff, which is an ongoing process that never ends, that we still have the same same discussion that that we had 12 years ago. But that that 20 work order was so sweet memory in my mind, I still if anybody asked me, what’s a breakthrough, that was the breakthrough? I don’t know if that didn’t happen. And I didn’t see any worker coming for a few more months, I would just, you know, shut down and say this, it’s not worth doing. I don’t know, I don’t know, what would have happened. But that is really big.

22:33

Yeah, it seemed like, you know, I just remember observing in it seemed like, you know, you had some very large enterprise customer interests. And in part of the, I think getting, building that confidence, you’d see it, you know, with every order almost in every meeting we had, and, you know, during the scale up, and it just seemed like the conversations, you know, the types of companies and the traction, you were seeing continued to increase as your confidence built, and kind of, I think more and more people believed in field nation, and it was a competitive space it you know, what, while you were starting, wasn’t it my No,

23:06

it was a competitive space, we had a, you know, very well funded competitors. And we did things very differently and not having money, I sometimes I say, you know, one of the one of the best thing is that don’t start with too much money. I mean, you need some money, so you’re not running out of cash, that’s a, that’s a different problem. But too much money could be the same problem. It could be, you know, a bigger problem, because you’re wasting someone else’s money without knowing whether you have the right product, or you have the right distribution, what not, and I’ve seen some of my competitors made that mistake of raising too much, I mean, the promise of a, you know, Uber, like model, and right now, you see everything is becoming Uber eyes, right. It’s the Uber of this and Uber of that delivery, and, you know, hotels, and everything is overpriced. And when we started in 2008, this idea of you know, getting on demand workers to go do something was new people would, investors are very bullish back then, as they are now. And so a lot of a lot of my competitors got raised a lot of money and they try to scale quickly without figuring out the you know, the market maturity and, and all that kind of stuff. And, and wasn’t wasn’t very successful. But you know, one thing I would say, the timing matters, right? So when we started people would compare us, Phil nation as the Craig’s Craigslist, they would say, oh, you’re like Craigslist. We are not we, you know, ABC Company. We’re enterprise. We don’t deal with Craigslist, right? And now it changed so much. It seems like everybody is more comfortable staying at Airbnb and riding an Uber. It’s the new normal, like, of course, you know, you get something on demand, that’s the way it was. It’s whether it’s a cloud on demand, or whether it’s a technician on demand on a driver on demand, it’s everything on demand.

25:21

That’s maybe a great kind of topic to follow a little bit, you know, we I know, you went a long time before raising, you know, any larger financing. And I remember working with young, young, young, young, everybody is now the Chief Strategy Officer at Samsung, he’s been there for six years. So quite, quite an amazing journey, you know, for the people involved in associated with that time, you know, going into that big financing. Do you want to talk about, you know, after you scaled for some time, you were in a position of strength, but how, what were you thinking about, you know, in terms of the next chapter, as you prepare for, you know, that your later financing, if you could share a little bit about that?

26:03

Yeah, you know, what, one thing we didn’t want it to do is raise a lot of money, too quickly. And because we were still, we were figuring it out at that time, like, what is the right market? What is the right customer? How do we scale them up? How do we scale our business and stuff like that, and there was, you know, we just didn’t want it to raise a lot of capital that comes with the, with the constraint of build it 100 people sales team and sell, sell, sell, you got to fight, you know, you know, you get to do that, you know, product market fit, you got to figure out the distribution channel and stuff like that. And so we waited, you know, we waited, and then we were adamant to find somebody who was genuinely passionate about the market we’re in and the problem that we’re trying to solve, and be patient, like we are, we know that it’s a slow maturing market. For us, it’s a slow maturing market, it is still taking a long time for us to, you know, see the market maturity, because we are working, we are working with enterprises and not consumers, it doesn’t turn, like the way you see GameStop it’s done. Yeah. enterprises move in a different pace. So we wanted to make sure that our investors are patient, they will stay with us and not not have that undue burden that, you know, do something because we got an exit, we got to figure out an exit in next, you know, next year or something like that. So when we raised our capital, that is, you know, end of 2015. By that time, we were on in 500, multiple times, fast 50. And so there was a lot of calls, we’re getting a lot of VC and private equities are coming from east and west coast. Unfortunately, there wasn’t any anybody from the, from the Midwest at that time. But I remember our CFO and I, we met 70, some VCs at that time, as part of the interview process. And then we finally found someone, a company private equity, called SAS corner growth equity. We immediately like those guys, because of their flexibility in the, in the capital and the life, the the time horizon, they have, they literally don’t have time horizon, if they’re like a business, they hold it, and they can have subsequent rounds, and stuff like that. And, and so we decided to raise capital at that time, you know, and up to those.

28:41

I remember always hearing you say that, you know, this is the startup you see yourself working on forever, you know, and it’s been, you know, I never thought you would, I never thought it would be come forever, but you still have the same excitement and patients it seems and continue to grow. And it’s been exciting, you know, following your journey, maybe we could kind of shift gears and talk a little bit more about the broader kind of gig economy, you know, and, you know, when when we started the fund, with experience investing in these gig like services quite a bit as angel investors, you know, we, you know, we’ve done SAS and marketplace, businesses, consumer and enterprise, as a fund. But, you know, we were excited to win starting the fund to get a group of operators as advisors of scaled tech companies, including yourself, so you know, having, you know, having then seeing in the portfolio, we start seeing a wide variety of, of people working on Uber like services for other markets and including one that you helped with diligence on early I remember, it was just so, so amazing to see this, this founder, Patrick O’Reilly at factory fix, you know, request a meeting with our fund and in his deck as he’s going through it. He says the comps he was highlighting was field nation as a major success. I was like Yeah, that’s my buddy, my Neil from college. He’s like, What? He’s like, yeah, I asked him if you mind if my noodle gets involved in reviewing this deal with us? And he said, Oh, sure, of course. But, you know, and that’s, you know, you know, your perspective as an operator, scaling a good leg service, and seeing different strategies play out has been invaluable, you know, in supporting our evaluation of such opportunities as factory fix. But do you want to talk a little bit about, you know, what you see as some of the different strategies and in, you know, that are working or not working with these types of services? With with kind of gig economy, kind of, yeah, what challenges and in what, what seems to be what are some of the key takeaways you see from people that have been successful and not successful in? How does it vary by market?

30:49

Yeah, I think the, on the consumer front gig platforms are really, really successful. I think the laggers are the enterprises. Unfortunately, we are in the, in that in that group, that enterprise will, but that’s, that’s catching up. Usually, that’s always the case, people in their personal life will experience something, and then they’ll they’ll think about, you know, how does it apply in their businesses and stuff like that? So, you know, there’s a lot of, you know, kind of consumer centric gig platforms from Uber and Airbnb to, you know, grub hub to everything else that you can you can think of, but the next frontier is that enterprises, the enterprise is thinking, you know, how can I reduce my capex and OPEX? and make it more variable? Right? I mean, and, you know, if you remember, Ryan 2008, was a great recession. Yeah, it was, it was good. I mean, it was good for us to start at that time, because everybody was thinking outside the box, like what, you know, any, any financial crisis kind of creates that sense of thinking outside the box, like, we got to change, right, the status quo is not good enough. So 2008, we saw a lot of, you know, SM B’s was whether, because of the need for survival or whatnot, they were thinking outside the box, and we saw great adoption, you know, since 2009, till, you know, many years. And what we are, we are we are seeing is that this crisis, the crisis we are in the pandemic crisis is shaking up the enterprises, and they’re thinking like, Okay, we got to think outside the box in terms of, you know, variable labor. And that’s the, that’s the next wave in the I’m talking more specifically about the labor platforms like Phil nation, and others. And, and they’re much more comfortable in their understanding of the labor model. It does has its its challenge, though, you know, you know, and the biggest challenge is that the worker classification in this country, there is literally to classification and none really fit well, with the gig workers, we have the W two model the full time employees, and you have the independent contractor model. And the challenge is that, you know, some states are trying to push gig workers to be classified as employees, you’ve probably heard, you know, Eb five, assembly bill five, buy from California, although, I think there is a proposition that that got passed last November that AV five didn’t go through ultimately, but if I would have made every gig worker, employee, but that’s not gig workers want, you know, they don’t want to be employees, they want the the number one thing that gig workers really enjoy is, is the flexibility and employment, you know, full time employment doesn’t give that. So there needs to be a new type of legislation to accommodate for this new class of, you know, workers, and they do need some safety, they need benefits, they need, you know, fair treatment. But but that’s the, you know, making everybody a full time w two is not the solution. So, I would say we think that we’ll see some legislative changes, you know, next, you know, few years, hopefully, will be a more common sense approach than say, you know, move everybody make them everybody don’t. Yeah, it’s not a solution.

34:52

Yeah, it seems that regulations are struggling to keep up with the pace of technology. And this is a shining example of that, but I think I think it’s really interesting what you said about the enterprise market and in today’s environment as well. I know, we’re running up against time here. And I just want to say thank you for, for your friendship and for sharing this journey together. It’s been amazing and appreciate you being one of our first guests on on the show. And I will turn it over to Joe to take us through the next section. Thanks.

35:26

Yeah, thanks so much. My new will in a second, I’ll open it up to everybody for q&a. But I just like to kick it off with the first question. We’ve been asking everybody who comes onto our podcast? Are there any founders or startups or like organizations, or people you see supporting founders and startups that are really executing? Maybe people here? Haven’t heard of them? Maybe they have heard of them? Maybe it’s someone where, you know, maybe it’s a branch or something that everybody’s heard of, but is there anyone in particular that you see that you think is really, really just killing it?

36:01

Joseph? that’s a that’s a great question. I can’t answer that with with a lot of firsthand experience. I do hear people, you know, join young presidents. I don’t know it is a club or some some Association there is, you know, people go and get advice and stuff like that. And, but in Twin Cities, I haven’t been part of anything that that, that I could say.

36:31

Well, thanks. Yeah, well, we’ll open it up to everybody here. If you guys have any questions, or just want to pop on your video, pop off your microphone and chat a little bit. Feel free to talk ask wave for any questions for my Newell and Ryan.

36:46

And one question, I was just gonna ask my Newell, you know, you went through a lot, you know, with the immigration process, you know, what do you think of the current kind of regulatory environment on immigration? And I guess, do you have any, you have a solution that you think would work better in terms of American immigration policy? You know, after having gone through the whole experience that you had?

37:10

Yeah, it’s also a very sensitive topic, isn’t it? Look, I think, I think we need to have a common sense approach to immigration. It’s people try to, you know, make it a binary problem. Nothing is a binary problem. It’s way more complicated than this, this right. And, look, I can tell you that a smarter approach would be looking at industry by industry and look at what kind of, you know, workers we need. This country needs, high skilled workers to notes, no skilled workers. I mean, it’s every everything in between. and but there is no, there is no systematic approach to address that problem. It gets a it becomes a very slogan type of approach. Rather than, you know, this dramatic market based I would make it a market based approach, you know, what is what is very difficult for me to get my head around is that think about some of my friends, we went to St. Cloud state we got institution because the taxpayers the Minnesota taxpayers paid for our some of our tuition right under there was a great help. Many couldn’t stay in this country, because of the complexity of immigration, guess what some of them went back to India and other parts of the world and working for, you know, Google and, and Microsoft sort of the world and paying taxes in those countries. So and so there is a vicious loop for us and a virtuous loop for other countries, meaning the US companies cannot find talent here. They’re gonna go wherever the talent is, whether it’s in other parts of the world, and that talented, they cannot stay here, guess what, they’re gonna go somewhere else, you know, and, and the companies will follow the talents and, and those talents will, you know, pay taxes and enrich their community and stuff like that. So, you know, market driven approach would be my, my approach my my recommendation.

39:29