by Graeme Thickins

Not surprisingly, the more established a VC firm, the more startup pitches it gets. Well-known VC partners get hundreds and hundreds of unsolicited pitches every week. But the real essence of deal flow for a VC is getting to see only the best of the best startups. Of course, that’s easier said than done. Deal flow is not about quantity – it’s about qualified access. The most successful VCs have perfected their deal flow process over years. How they do it is all about track record and experience — brand if you will. The case we make here is that, above all, the best deal flow comes from relationships.

First, let’s dissect the term. One definition is this: “deal flow” is the process by which investors attract potential investments, narrow down those opportunities, and then make a final investment decision. More broadly, it refers to the pipeline of potential investment opportunities – both the rate at which opportunities are received and the quality of those opportunities.

Brad Feld of the Foundry Group once referred to it this way on his blog: “Great venture firms don’t just wait for deal flow; they cultivate it.” Another famed VC, Chris Sacca of Lowercase Capital, has frequently made this point in podcasts: “Most of our best deals came through warm intros. Networks matter, because that’s where the strongest founders tend to circulate.” The message is that the best deal flow comes from the quality of one’s networks, not the quantity of pitches alone.

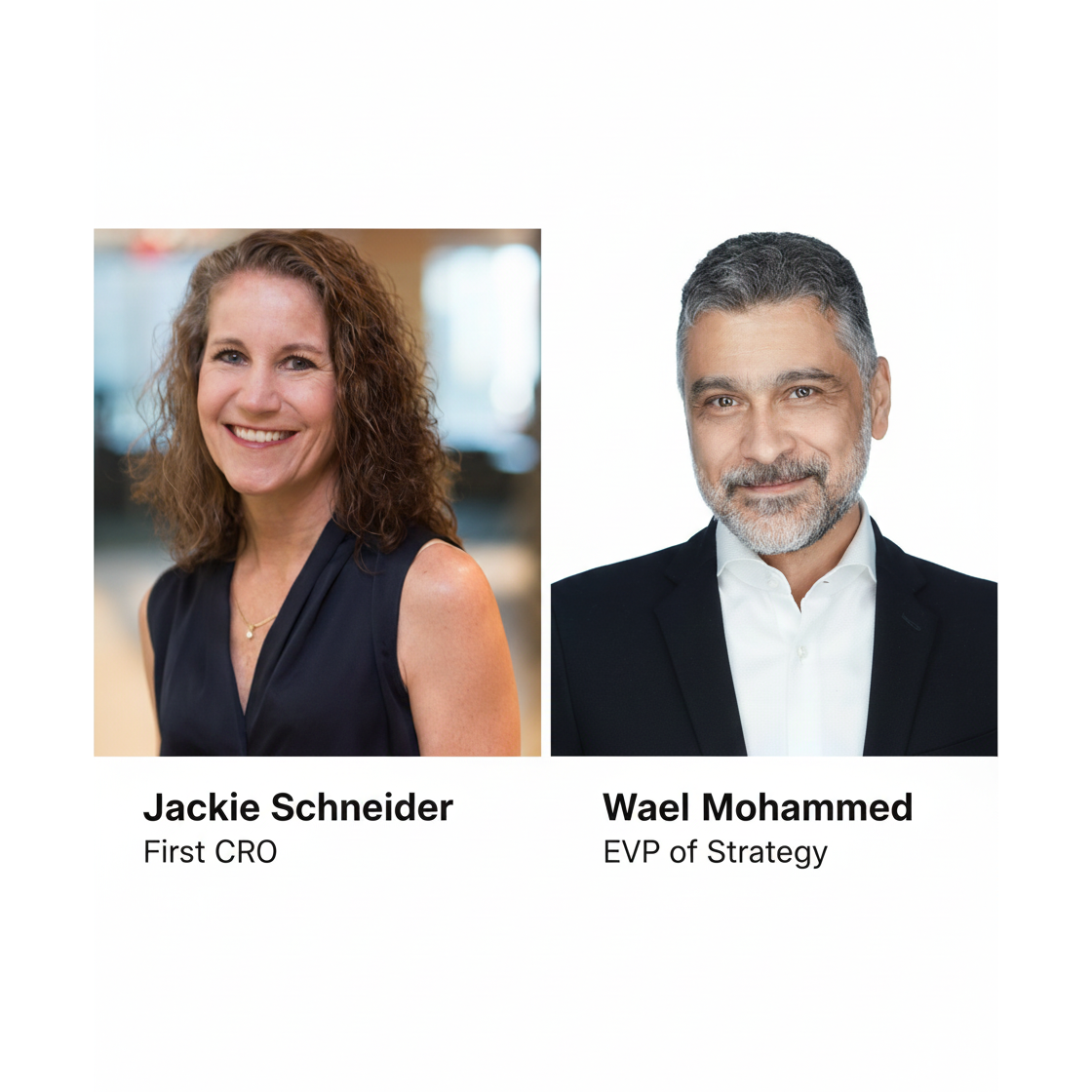

The founding partners of Great North Ventures, Rob and Ryan Weber, have their own take on what deal flow has meant for them over almost 20 years of investing. That was first as angel investors, where they realized a 7X cash-on-cash return over 10 years. “After that success, we created a venture fund because we had such good deal flow we wanted to share it with our friends,” said Rob.

How did they see such great deal flow as they developed as investors? “Much of it was due to the strength of our networks from scaling our own operating businesses,” said Rob’s twin brother, Ryan.

The point is this: the network of relationships they developed through building their own companies was a strong source for deal flow as they launched their venture firm, which has raised two funds, the first in 2018, followed by a second in 2022.

How Do VCs Think About Getting to Know Founders?

Some 15 years ago, VC Mark Suster of Upfront Ventures wrote a post entitled, “Invest in Lines, Not Dots” on his blog, Both Sides of the Table. What was the gist of that post? Suster argued that great investors do not evaluate companies as isolated snapshots (“dots”), like a pitch or demo, but instead look for trajectories (“lines”) – patterns of progress, learning, and execution over time. In venture capital, returns come from backing teams whose rate of improvement compounds faster than the market expects.

Mark’s advice is even more relevant today, the Weber brothers submit, given the volume of cold, AI-written solicitations that founders are lobbing into VCs’ inboxes these days looking to raise money for their startups. That pitching approach is certainly not the formula for fundraising success, they say, in a world where relationships and networks matter more than ever. Founders need what the Webers call multi-touch connections, which naturally develop over a course of time.

Touch Points Matter

What are some examples of how the multi-touch approach has worked for the Webers? One is a portfolio company of theirs called Branch. Before they invested, the Webers had three strong connection points to this company, founded by Atif Siddiqi. It was part of a Techstars cohort, an accelerator the Webers knew well. A partner at Crosscut Ventures, Brett Brewer, which had invested in Branch, had a history with the Webers through Intermix, the incubator of MySpace. IdeaLab, where Branch began in LA, had a past connection to the Webers through their work with GoTo(dot)com/Overture, which was acquired by Yahoo.

Another example: Andrew Wegrzyn, a partner at VC firm SixThirty, which is focused in fintech, introduced the Webers to Timothy Li, the founder of LendAPI, a recent investment in the Webers’ Great North Ventures Fund II. Why was he a good referral source? He knew the Webers had a history of scaling businesses in a capital efficient manner from their days as bootstrapped entrepreneurs. He also had a common interest in the fintech space.

Yet a third example was Jon Dahl, the founder of Zencoder. The Webers already knew Jon through mutual entrepreneurial friends in the Twin Cities. Chris Sacca of LowerCase Capital invested in Zencoder soon after it was chosen to be part of a Y Combinator cohort in Silicon Valley. The Webers had been introduced to Chris while he was at Google. Just months after the Webers also invested, Zencoder had a major exit when it was bought by public company Brightcove in 2012.

There are other examples of how network connections led to positive deal flow for the Webers, and successful exit outcomes:

• Neurotic Media was an investment of the Webers’ that was sold to Peloton in 2018. It was originally referred to them by Jim Wehmann, who at the time was an executive at Minnesota-based Digital River.

• HomeSpotter was founded by Aaron Kardell, whom the Webers had met through their local Minnesota networks. He was inspiring local developers to develop apps for iPhone soon after it launched in 2007. Initially, his business model was creating white-label apps for realtors and brokers, and the Webers invested. That was a nice initial business, and he would expand successfully with other products. HomeSpotter was acquired by Lone Wolf Technologies in 2021.

• Field Nation was founded by Ryan Weber’s computer science lab partner at St. Cloud State University. The Webers invested early on and had a major exit when the company received a $30 million investment from Susquehanna Growth Equity in 2015.

Of course, there were many other great deals the Weber brothers sourced but unfortunately did not invest in, as I wrote about in a recent article that explored the notion of the “anti-portfolio.”

In the Webers’ angel-investing experience, they had deal flow that produced a 7X cash-on-cash return over just 10 years, even though they were only writing $100K checks per deal. That success caused them to want to scale their investing business to provide access to more winning investment opportunities,

That ability to create and perfect good deal flow early-on led the Webers to found Great North Ventures and raise their Fund I, which closed at $24 million in 2018. Seeing success with that fund, the brothers successfully raised Fund II, which closed at $41 million in mid-2022.

What Are the Implications for Founders Today?

The Weber brothers prioritized and achieved positive deal flow over 10+ years of angel investing, then followed with more of the same during eight years (and counting) while running two VC funds at Great North Ventures. One important lesson for them over this time has been the requirement for patience.

But the brothers have learned some things over those two decades of investing experience that are also informative for today’s founders. I asked Rob Weber, “How can entrepreneurs be more successful at fundraising today?” His advice was three-fold: “One, don’t cold-solicit VCs. It doesn’t work, especially in the age of AI. Two, your first impression matters. And, three, seek introductions through the most credible common relationships you can think of.”

Twin brother Ryan Weber added this advice: “Multi-touch is better than single touch. If you have multiple common relationships with us, it can be worthwhile to make those connections known. We had multiple connections leading to our investment in our portfolio company Branch, as we mentioned.” And he emphasized the point made in that famous “Lines, Not Dots” blog post referred to earlier. “Work on developing VC relationships over time.” Specifically, he said, “Plan on meeting with a VC several months before you begin your raise. Provide updates on your progress from time to time. Monthly is typically good for early-stage startups. Keep at it with those.”

All in all, one thing is true: the more founders understand the concept of deal flow, and the way VCs approach their work and value their relationships and networks, the better off they will be as they seek to raise funding in today’s environment.

———-

Graeme Thickins is a startup advisor and an investor in Great North Ventures Fund I. He is also an angel investor in two subsequent Great North portfolio companies. He has written previously for and about Great North Ventures and its founders over several years.